The proposed aid measure raises a number of questions about the necessity, proportionality and adequacy of such support, which are outlined below. Further details are provided in the summary translated into all official EU languages, as well as in paragraphs 71-106 of the full Commission decision – see links below.

Public consultations — State aid: Italian digital cinema tax credit

Summary of decision to open formal investigation into Italy’s proposed digital cinema tax credit

Decision letter sent to the Italian authorities

=-=-= =-=-= =-=-= =-=-=

The EDCF, the European Digital Cinema Forum, sent the following answers to the above queries by the Commission. The PDF version is at: EDCF Answer to the Questionnaire from The European Commission on the Italian Project of Tax Credit for the Investment in Digital Cinemas

European Commission

State-aid Registry

Directorate-General for Competition

B-1049 Brussels

Fax: +32 2 296 1282

e-mail: [email protected]

Ref: C25/09

EDCF ANSWER TO THE QUESTIONNAIRE FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION ON THE ITALIAN PROJECT OF TAX CREDIT FOR THE INVESTMENT IN DIGITAL CINEMAS

Introduction

EDCF is the pre-eminent forum for sharing of ideas, information, questions and news about the business of D-cinema in Europe and continues to play a pivotal part in bringing together its members to enable the smooth and effective use of the new equipment and tools.

Members of EDCF share their experiences for the benefit of the industry as a whole. Membership is open to all with a technical, commercial or cultural interest in digitalcinema and includes exhibitors, distributors, manufacturers, broadcasters, service providers, regulatory authorities, industry associations and governmental bodies.

Why, from its membership, is EDCF fully entitled to answer the questionnaire? EDCF in itself does not manufacture or sell hardware, software produce or distribute films, etc. It is a forum for discussion on the topic of digital cinema.

Firstly ECDF will present its answers to the questionnaire and will follow this with comments on the points raised by the European Commission in its letter to the Italian government. These comments will expand on the EDCF’s answers to the questionnaire.

EDCF will focus its answer on the points which it considers as part of its field of competence and therefore it will not comment on the principle and formulation of the Italian State aid under the form of a tax credit.

I – ANSWERS TO THE QUESTIONNAIRE

Outline of questions raised by the Commission:

1. Is €100,000 per screen a fair estimate of the cost of installing digital projection equipment? If so, is it affordable even with State aid?

EDCF does not participate in commercial affairs but the cost of equipment has reduced as volumes have increased and new models for smaller venues have been added. We would have expected total costs to have been nearer to Euro 75,000 for an installed system that includes a server, installation and upgrades for the sound and ventilation systems. Installation costs will obviously vary according to the state of the booth and equipment. It is normally the case that exhibitors take the opportunity to ensure the sound, electricity and ventilation systems are adequate to handle the new equipment. In some cases new port holes have to be created or modified to add the digital projector. Another cost is the provision of interfaces to enable ‘Alternative content media to be delivered to the projector.

Yes, as we mentioned above, the cost is a conservative estimate of the full cost: projector, server, improvement of the projection booth, cabling, improvement of the sound system. For some operators costs will be less depending on the physical situation in the projection area, current condition of audio equipment etc. Some operators may be able to cover the cost themselves or in sharing the cost with film distributors or providers of alternative content. However the business situation of some operators, even with these contributions, makes them unable to cover this cost.

2. Are there no commercial business models which could install digital projection equipment at least in the more profitable cinemas?

There are commercial business models for the installation of the equipment. Some cinemas do it with their own money. Others are asking a contribution from the providers of content, mainly film distributors, under the form of a VPF (virtual print fee) monitored by a third party or directly. Currently, in Europe VPFs are available only via third parties. The concern of the industry is to organise a smooth transition period: State aid can help achieve this.

3. Would audiences find a wider choice of films at those cinemas receiving State aid for digital projection equipment? If not, what is the advantage to the taxpayer?

Yes. With digital projection there is no longer a 35mm print held in a cinema: the film is in a server. Therefore it is possible to offer more films or more screenings of the same film over a longer period of time, subject to normal business negotiations with the distributor, than when the 35mm print has to be given back to the distributor or sent to another cinema. It appears that the smaller cinemas currently offer the broadest choice of movies. These are the cinemas that have the biggest difficulty with the VPF model which is best suited to screens showing fewer films that have bigger box office success. The VPF model also depends on print cost avoidance which doesnot happen with those cinemas that run movies after they have already been used on first release circuits.

4. It has been argued that, if they cannot afford the equipment, many cinemas could close when film distributors switch from 35mm to digital.

How real is this threat and what is the timeframe?

The concern is a double one: film distributors would have to provide both 35mm prints and digital files for a long period of time, reducing the savings coming from digital projection (which actually only kick in after a VPF deal is finished) or some cinemas would have a shorter choice of films. At some point in time, all films will be available only digitally, that is at the end of the transition period. It is likely that 35mm will be available for some time to come, even if in limited form, but it is clear that 35mm will become more expensive as the volume provided to the industry goes down, and that providing 35mm will at some point prove prohibitively expensive.

Would one-off State aid provide a sustainable and uniform solution for digital cinema? In particular, would the cinemas which could not afford the equipment without State aid be able to meet the apparently higher running costs of digital projection equipment and replace it at the end of its useful life?

The question of additional running costs is unclear. Some costs may well be higher, but the cinema owner gains the possibility of new revenue streams

5. Would cinemas be induced by the State aid to invest in one digital standard in preference to another?

Cinemas should be induced to invest in the standard allowing the projection of all kinds of content. It is in the business interest of cinemas not to be prevented from showing some content! Systems fulfilling the requirements of the ISO standard achieve this.

6. As a condition of the State aid, would cinemas have to ensure that films released in any open digital format could be screened on the supported equipment?

The film industry has been active in the definition of the ISO standards for digital projection. Film distributors and cinema exhibitors welcome a standard allowing the same universality of use as can be achieve with the 35mm print.

‘Any open digital format’ would add cost to the project as there are so many. Equally importantly the multiplicity of format options increases the complexity and opportunity for error. Even with the rigidly defined D Cinema standards much work is going on to eliminate the opportunity for errors in settings for the presentation. In the longer term many of these settings will be applied automatically through Macro definitions which are embedded in the data streams but this phase is still being worked on by the implementation bodies – mainly ISDCF (the Inter Society Digital Cinema Forum).

7. In view of the limited number of cinema screens worldwide and the limited production capacity of projection equipment designed specifically for cinemas, would State aid for such equipment artificially inflate its price?

This is a fair question for the Commission to ask. In the USA the VPF contribution from the major motion picture studios towards total exhibitor equipment costs is much higher than is the case in Europe. This is because European exhibitors play a lower percentage of major studio content. (varies by country). The studio argument is that each user of the equipment should pay its proportionately fair share of the costs. The smaller exhibitors in Europe are thus unable to get the lion’s share of the digital equipment funded by the big box office movie creators and distributors. Ultimately, the VPF model provides a fair attribution of cost when box office is the determinant of contribution. When ‘choice’ and ‘diversity’ are the parameters of contribution the VPF model discriminates against the short run, less successful movies and this is where many of the culturally valuable movies find themselves. Hence the need to enable screens to show these movies digitally amidst the high profile sales campaigns of the major studios showing ‘popular’ culture.

EDCF therefore believes that whilst any form of state aid for procurement potentially can inhibit free market price decline, the benefits for cinemagoers in enabling more choice and the preservation of local culture movies is paramount. Manufacturers are already competing aggressively for the market and we do not expect state aid to have any material impact on the competitive activity or prices. Arguably, the increased purchase opportunities are as likely to stimulate even more competitive attention and bidding.

8. In connection with questions 4, 5 & 8, could State aid for digital cinema accelerate the closure of the least profitable cinemas?

On the contrary, we would say that the absence of State aid would accelerate the closure of some cinemas!

——————————————————————-

II – COMMENTS TO THE LETTER SENT ON JULY 22ND, 2009 TO THE ITALIAN GOVERNMENT

We refer to the numbers of the paragraphs of the letter1. (1Commission Document C(2009) 5512 final of 22/07/09.)

Digital Cinema tax credits

(72) The Commission itself has supported the equipment of some cinemas through the EUROPA CINEMAS network

Necessity

(74) Support for digital projection is necessary because distributors will potentially move quickly to electronic media once a critical mass of screens and films is reached.

The concern that we have in the EDCF is that the investment required to use digital equipment is relatively independent of a screen’s box office revenue. The smaller exhibitors require the same technology equipment but cannot recover the capital and installation costs so quickly, if ever. Many of the smaller operators find their place in the market by offering ‘special interest ‘ and more varied and culturally diverse movie programming. These operators are at the greatest risk of being left behind in the transition to D Cinema and this threatens the venues that currently support the ‘more cultural’ productions.

Up until now, the so called ‘Alternative Content’ that becomes deliverable to audiences in D Cinema equipped theatres has yielded little revenue. This is for a variety of reasons – lack of standards, lack of technical knowledge and equipment and inadequate marketing. These shortcomings are being better understood and promise to become more important over time. This will contribute to an answer to the question raised in paragraph 96 about the longer term viability of survival of the smaller theatres once they have initial systems installed.

It is also necessary for theatrical cinema to consider the general progression in the delivery of higher quality audio and image quality. It is necessary to remain competitive with other entertainment formats such as TV, home cinema and even hand-held portable devices to maintain an ongoing viable market position. Cinemas of all types must move the quality of ‘the cinema experience’ to stay competitive and thus remain viable.

Digital cinema allows exhibitors to offer more films and more screenings of those films. Currently the cost of 35mm print drives a distributor to require that the movie is screened for a minimum time period. This doesn’t always serve the exhibitor’s interests if the film doesn’t produce expected box office performance.. With 35mm print, an exhibitor tries to return the print to the distributor when he thinks it has reached the maximum of its potential audience or if the distributor needs the print for another exhibitor. On the contrary with a digital file downloaded to a server, the exhibitor may keep the film and organise screenings when appropriate, for example if a school wishes to show the film at a particularly suitable time, subject to distributor agreement.

It is now considered that 3D is going to be a new paradigm for the cinema experience. 3D requires as minimum digital equipment at the ISO TC36 standard. Many animated films are now in 3D and some eminent film directors, ranging from Wim Wenders to James Cameron are using 3D to better express their artistic vision. 3D will soon be available for television at home: how can it be imagined that viewers will not expect the same in cinemas? Techicolor have recently announced a 3D upgrade option for film projectors. This underscores the perceived importance of 3D presentation but we believe that Digital 3D will be the preferred format over time.

(75) In this paragraph the Commission understands the improvements coming from flexible programming, therefore answering the questions raised in the previous paragraph.

(76) There is an inevitable simplification in the claim that D Cinema has been slow to be installed because of the high costs. In the early days (2000 – 2003) exhibitors were unsure about the D Cinema future while producers were yet to be convinced about the performance relative to the ‘gold standard’ of 35mm capability. Then (2003 – 2007) the lack of a standard threatened a potentially shorter useful life. On top of these concerns was the more complex problem of the cost savings benefiting the Distributor whereas the Exhibitor had to make the capital investment. The industry has always operated in a state of mutual tension and dependence so the negotiations were always strained and thus slow.

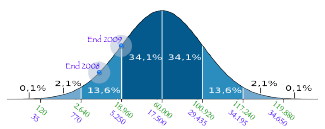

The question of the ‘slowness’ of the industry may be answered by the annexed chart: it shows that once the DCI specifications have been adopted the trend of equipment of cinemas has raised, clearly showing the need from the industry to be able to use an agreed form of standardisation. We may also remember the time it took for VCRs to go into the houses: every six months a new system was announced so consumers were waiting.

There are now globally agreed ISO standards. These have been created in consultation with the industry. Debate and consultation has taken place in recent years at industry conferences such as IBC, NAB, I-DIFF, IMAGO, ECS and CinemaExpo and each national member represented their local industries in the ISO meetings. The inclusivity of the standardisation process is notably evidenced in Europe by the inclusion of frame-rates specific to Europe. Manufacturers are now building equipment to these standards.

General models are available to fund the equipment for the major exhibitors – through the VPF mechanism or variations thereof.

The promise of Stereoscopic 3D movies is providing a clear commercial logic to move forward.

Were it not for the global economic crisis there is little doubt that deployment in the major chains would be moving on a much faster trajectory.

But none of these arguments is helpful to the exhibitors with the smaller box office revenues who often serve the more remote communities with a diet of more ‘national’ culture movies. These operators are threatened by the new technology in the period of transition.

(77-79) Cost of equipment is clearly a barrier to broader deployment. Doubtless others with a commercial interest will comment on the accuracy of the Euro 100,000 price tag. There does appear to be a widely held misconception that the cost and thus price of D Cinema systems is a direct function of the spatial resolution that is specified for compliance. It is a much more complex reason than that: D Cinema systems were initially developed because the movie industry knew that film costs were escalating, required scarce resources (silver) and used environmentally unfriendly materials (bleach, developers and fixers). As movies had a limited life in distribution they were also not easily recyclable and thus wasteful.

These factors would all lead to increased costs over time. On the other hand digital media had a rapidly declining cost trajectory and used recyclable technology – further reducing costs.

The challenge in the mid to late 90’s was to convince the creative community (Producers, Directors and Directors of Photography) that the new technology could offer the same image quality as 35mm film. That image quality was multidimensional, but could be simplified to three main elements – Contrast, Colour and Consistency.

The nature of film technology is that the chemistry and processes tend to deliver a level of consistency that could be managed by the movie business in sharp contrast to the TV world where a variety of cameras, transmission systems and mostly television sets were outside of the control of program makers and broadcasters.

Television (and video) thus achieved a reputation for loosely controlled image quality.

This perception (of video) still remains a major hurdle in the creative film community with regard to digital image capture but the development of a rigorous electronic projection technology has satisfied the community that it is now good enough to replace film for show-print distribution at least. The provision of high contrast, accurate colour and short and long term consistency has specification implications in the optics, thermal management and electronics. These requirements have implications for projector component costs. The final element in the provision of a practical and deployable digital cinema system was the integration of a robust system of data protection to minimize if not eliminate the possibility of content theft from the projector electronics. Normal home cinema and large venue projectors do not carry this obligation which also has a cost implication.

Apart from these fundamental requirements of a D Cinema projection system (which do not relate to spatial resolution e.g. 1.3K, 2K, 4K) the specifications also make provision for graphic overlays to support more flexible and easily readable sub-titles.

An important consideration in the definition of the D Cinema specification was that the change from Film to Digital technology should be one that would not soon become obsolete because of the rapid pace of new technology. This was the motivation for a two way compatible 4K option for film makers.

The recent announcement by Texas Instruments to offer 4K technology (previously only offered by Sony Corporation) not only brings more competition to the higher end of D Cinema but may also herald more cost effective 2K systems in the future as competitors vie for the market.

The D Cinema standard was thus widely accepted by the movie industry as an expensive but necessary evolution to provide a sustainable asset for a justifiable period of time.

While lower cost projectors seemingly offer similar capability, that appears acceptable by most patrons they threaten a progressively weaker and less compelling ‘out of home’ theatrical experience which is likely to be surpassed by home systems and are likely to degrade over time due to less stable component technologies. As an example most consumer camcorders now offer ‘Full HD’ recording capability. Many TV sets also offer Full HD native spatial resolution images. Full HD is 1.9K in the current parlance, so it would seem that the often requested 1.3K option would not provide a marketable option even if it produced satisfactory image quality.

It is also worth mentioning that projector costs are highly related to brightness and cinemas require both luminous power and dependable performance just like the 35mm technology they are replacing. A new demand on this optical power is being made by 3D capability where the optical efficiencies of the shuttered systems require as much as three times more light output.

The Commission recalls that the cost includes the projector, the server and the installation in the cinema. In some cinemas it is necessary to renew the sound system: it has to offer 5.1 quality and sometimes the existing sound system is sub standard.

Sometimes the projection booth must be updated including: cabling, air conditioning, etc., which may quickly add to high figures because of architectural reasons. So the figure of € 100.000 for a complete installation is considered as a reasonable average.

More particularly in paragraph (78) the Commission raises the point of the cost for all the cinemas in Europe, wondering if in the present economic climate the sum of € 3.3 billion would be available. No one seriously thinks that all cinemas will convert so as to justify that amount of money over a short period of time. The question of the slowness of the industry has been raised above. It is considered that the transition period would last some ten years. A € 300 M investment does not seem to be impossible on this timescale.

(80) It is true that many forms of alternative content have been tested in cinema environments. These have been done in some cases with standard definition TV signals and lower cost projectors. It may well be that the public accept these systems for certain special events but as HDTV becomes more prevalent, systems installed today may soon become unacceptable and this represents a poor investment for cinema owners. Some operators have used lower cost systems to deliver advertisements but these have not been long lasting and many have already been replaced. Cinema operators want a single system that can deliver all forms of content without the need for specialist on-site engineers. This drives demand for omnicapable technology not low cost individual systems.

(81) It should be mentioned here that D Cinema Compliant 1.3K projectors are no longer available. Manufacturers are building 2 K and 4K projectors. To be more accurate the 1.3K D Cinema Projectors that were produced using Texas Instruments DLP Cinema technology were never ‘DCI’,’SMPTE’ or ‘ISO’ compliant. They were the forerunner to the formalised standard in 2005 by DCI. Once 2K was established, manufacturers switched to 2K or 4K versions. Studios accepted the first 1.3K projectors for screenings during a grandfathering period to allow the upgrades to be made to the required standard.

(82) Some movie makers may be prepared to have their movies shown on lower quality equipment but the necessity is to have a single system capable of playing all formats. It makes no sense to install individual equipment each suited to different standards.

It is worth noting that the ISO TG36 D Cinema standard is the only one which provides a complete definition of how content should be presented to an audience. The HDTV technologies have a multitude of standards for compression, encryption, data-rate and have no process for the presentation needs of theatrical venues where screen brightness uniformity and sound presentation is a fundamental consideration. Those systems have been developed for TV receivers not public venues.

3D movies are more expensive to produce and the technology is still very new. Expect this to change rapidly in the next five years so 3D ready equipment should be an important consideration for all theatrically delivered content.

Film makers want the best quality for their movies. Sometimes for artistic or financial reason they shoot their films with light cameras but post production expenses still remain high2. We do not accept the point that European film makers would be happy with lower standards than their American colleagues. Would it be possible to explain to the public going to a cinema that the European film it is going to see is on a lower standard than an American film? Besides this, 3D is just beginning and some European directors are beginning to think about using this technique.

(83) It is important to consider the luminous output and not just the spatial resolution. The “2K spec” not only covers resolution but also includes standards for compression, colour, contrast, encryption and audio.

Proportionality

(85-89) The EDCF is concerned that support is provided to the smaller operators who are threatened by their lower box office revenues and who typically screen more cultural content than some but not all of the major operators.

(89 & 96) It is clear that the major US based studios recognise that International markets such as Italy show a lower percentage of their content and the virtual print fees offered will thus be lower than in markets showing more Hollywood content. It would seem reasonable that local producers should contribute a proportionate share of the costs to exhibitors. But this is a chicken and egg scenario and contributes to the argument that the proposed measures are needed for a limited transitional time period.

(91) One of the difficulties that smaller local producers face is the cost of 35mm film prints. As a result films are printed in limited volume and then circulated over an extended period. Digital technology offers lower distribution costs which then makes more effective marketing possible because ‘wider’ releases are affordable. This would provide significant benefit to local production companies making ‘Italian’ movies more successful. One can assume that important distributors releasing films on a large scale may benefit from better prices for 35mm prints than small distributors releasing films with a few prints. The savings on cost is proportionally higher for small companies. This has been shown in the report published in April 2008 by Mr LEVRIER for French CNC3. Besides this the way films are scheduled in a cinema changes when digital technology is present: the ‘long tail theory’ applies and distributors no longer have to move a print from one cinema to another. A successful arthouse film may stay much longer in a cinema than it can today.

Footnote 2) Acclaimed film makers such as Abbas Karostami or Alain Cavalier have created masterpieces using handheld cameras.

Footnote 3) <www.cnc.fr/Site/Template/T1.aspx?SELECTID=2955&ID=2014&t=3>

(92) The ‘chicken and egg issue’ of no films because of no equipment needs a starting point to create a solution. The initiative to support the equipment of cinemas will obviously help. Some European film agencies require a digital master to be made available as a condition of support to film production. EURIMAGES provides financial support for the digital masters. It is true that these masters are not quite the same as those which are necessary for making DVDs or releasing films on VoD but at a point the source is the same. It has also been shown, for example in the ‘rappor LEVRIER’ mentioned above that small distributors would proportionally get more benefit from digital distribution than large companies. The market needs the impetus to organise the transition.

(94) Are VAT included in ‘all tax credits’. If yes the less viable cinemas would be able to enjoy this relief without generating such a significant Corporation Tax liability? Information received from our Italian colleagues shows that VAT is included in all tax credits. As all cinemas do pay VAT they would have the capacity to use their tax credit against VAT, even if they do not pay corporate tax.

(95) The lifetime of this equipment is as yet undetermined but will be a minimum of 10years – manufacturers are currently providing 10year warranties Economic, social & cultural impact

(99) EDCF agrees strongly with this statement.

(100) The ISO D Cinema Standards do not prescribe a specific technology in terms of how but rather what is required for adequate presentation of movie material. The standards are necessarily specific about the compression and encryption schemes to ensure compatibility and interoperability between components and manufacturers of servers and projectors. A completely ‘open’ system would afford no benefits to exhibitors. The standard of 35mm film was a constraint but one which did not restrict competition for film supply or processing. It did not attract huge numbers of competitors because it is a relatively small end market in comparison to that of television or camcorders for example. The same applies to the D Cinema business. It can be seen that many operators decided to equip their cinema once standards were available. Obviously some people are what we may call ‘early adopters’ and will jump on any new technology. Most decision makers will have a less proactive attitude to innovation and wait for a standard to be considered as a norm.

(101 & 102) D Cinema systems are all capable of screening less demanding standards although there are a host of choices which adds to costs. Work is underway to define a standardised approach to alternative content to cover other non-movie content for example EDCF has published a guide for alternative content (see www.edcf.net)

(104 & 105) We would need to understand the position of the Commission: sometimes it considers that the industry moves too slowly, sometimes it fears that if it moves too quickly the demand will be too high and cost would rise.

EDCF

Hayes House

Furge Lane

Henstridge, UK

BA8 0RN

44 7860645073

[email protected]

www.edcf.net

30th October 2009

1 Commission Document C(2009) 5512 final of 22/07/09.)

2Acclaimed film makers such as Abbas Karostami or Alain Cavalier have created masterpieces using handheld cameras.

3 <www.cnc.fr/Site/Template/T1.aspx?SELECTID=2955&ID=2014&t=3>