Summary

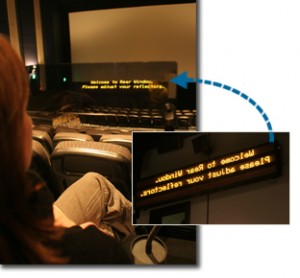

The Applicants request that the Commission grant them an exemption in relation to the provision of open captions of films for people who are Deaf or have a hearing impairment and audio description of films for people who are blind or have a vision impairment.

Derived from: – Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

AUSTRALIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION

DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION ACT 1992 (CTH), section 55(1)

NOTICE OF REFUSAL OF A TEMPORARY EXEMPTION

The Applicants seek an exemption for a period of two and a half years. The Applicants propose that as a condition of granting the exemption, the Applicants will progressively make a further 23 cinemas accessible. The Applicants also undertake to review the current program with key stakeholders nine months before the end of the exemption period and ensure that information on the screening times of captioned and audio described films is accessible.

The Applicants request an exemption in relation to the provision of captioning and audio description so that they can undertake a coordinated rollout of captioning and audio description technology rather than provide the technology in an ad hoc manner in response to individual complaints.

The Commission has refused to grant the exemption for the following reasons:

- The reasons advanced by the Applicant in support of the exemption are insufficient to justify the granting of the exemption.

- The progress in captioning and audio description proposed by the Applicants is insufficient both in the number of cinemas that will be enabled to screen captioned and audio described films and the number of times per week that this service will be available. This is particularly so given the financial resources apparently available to the Applicants.

- Any benefit that would result from the granting of the exemption is outweighed by the detriment that would be experienced by cinema patrons who have a vision or hearing impairment whose ability to complain about cinema captioning and audio description would be affected by the exemption.

BACKGROUND

The Applicants advise that collectively they operate 125 cinema complexes around Australia.

Nature of Application

The Applicants request a temporary exemption in relation to the provision of captioning and audio description for a period of two and a half years. The Application is sought in relation to cinemas owned or operated by the Applicants and affiliate companies as well as those partially owned by the Applicants.

The Applicants state that during the period of the exemption they would:

- increase the number of screens capable of delivering captions in cinemas operated by the Applicants to 35 over the next 2 and a half years;

- provide audio description capability in all those 35 cinemas (this would include a retro-fit of the 12 cinemas at which captioning is currently available);

- commit to a review of the current program in consultation with representatives from key stakeholders starting 9 months before the end of the temporary exemption period; and

- ensure that information on the screening times of captioned and audio described films is accessible.

Applicants’ reasons for requesting an exemption

The Applicants submit that a temporary exemption would allow them to take a planned, considered and co-ordinated approach to the rollout across Australia of the technology necessary to screen films with captioning and audio description.

The Applicants state that responding to complaints about failure to provide captioning and audio description diverts resources that could otherwise be applied to provide captions and audio description.

The Applicants also say that providing captions and audio description in order to resolve individual disability discrimination complaints leads to ad hoc provision of these services, usually in the complainants’ local cinema, rather than an even distribution of screens capable of providing captions and audio description throughout Australia.

Submissions received by Commission

The Applicants’ request for a temporary exemption was posted on the Commission’s web site and interested parties were invited to comment on the exemption.

The Commission received 466 submissions in response to the Applicant’s request.

11 submissions support the proposed temporary exemption and of these many noted that while the Applicants have been slow in increasing the number of cinemas that can screen captioned and audio described films the granting of an exemption would at least ensure that some progress would be made.

Of the submissions that express support for the exemption, several submissions argue that different conditions to those proposed by the Applicants should be attached to the exemption.

Some submissions focussed on the issue of audio description for people with a vision impairment and proposed different conditions including: that retro-fitting to provide audio description in cinemas that already have the technology should occur immediately rather than be rolled out over the period of the exemption, that audio description should be available wherever possible rather than at the three sessions per week that are captioned, that all new cinemas and those that are refurbished should be equipped to provide audio description and specifically that the Applicants’ websites which advise vision impaired cinema goers of screening times should be accessible in accordance with the World Wide Web Consortium Standards.

455 of the 466 submissions received by the Commission recommended that the Commission reject the application.

Most of the submissions come from Deaf people and people with a hearing impairment and their friends and family who highlight the importance of cinema captioning in enabling them to enjoy a popular form of entertainment with both Deaf and hearing friends. Many submissions emphasize that Deaf people and people with a hearing impairment need captions to access the service provided by the Applicants and failing to provide an accessible service amounted to disability discrimination.

Several submissions argue that rights under the DDA should not be ‘traded’ for the provision of captions and audio description. For example, one submission states that ‘whilst it is commendable that the applicants are apparently seeking to increase access, this should be something to which they aspire to as a matter of good corporate responsibility. It should not be something done in exchange for immunity from a complaint’.

A very large number of submissions contend that the Commission should not grant the exemption because it would effectively mean that people with a vision or hearing impairment would lose their right to lodge complaints of disability discrimination about cinema captioning and audio description for the period of the exemption.

Several submissions suggest that the Commission should not grant the exemption because the captioning service currently provided by the Applicants is inadequate. The Applicants screen one captioned film at a time, three times per week. Some of the submissions note that this schedule provides Deaf and hearing impaired cinema patrons with little choice in the films available to them. Other submissions note that the schedule for screening captioned films sometimes changes without prior notice being provided to patrons.

Several submissions also note that the issue of the provision of captioning for Deaf people and people with a hearing impairment has been ongoing since captioning technology was developed over 20 years ago. These submissions argue that the Applicants have had a long time to make an adequate proportion of their service accessible and they have not done so.

Many submissions argue that the rate of captioning proposed by the applicants is far too low and note the statistic that if three captioned films were shown at 35 cinemas around Australia, only 0.3% of the 40,000 films screened by the Applicants per week would be captioned. Some submissions from individuals from regional and remote areas note that the rollout proposed by the Applicants would not result in an accessible cinema near them.

One submission argues that the Commission should not grant the exemption because, amongst other reasons, the cost of captioning is relatively low, approximately $15,000.00 – $20,000.00 per screen. Another submission notes that reports have suggested that the Applicants are making a considerable investment in technology to allow the screening of 3D films. The submission argues that if the Applicants have funds for investing in digital and 3D technology, they have funds for making a greater investment in captioning and audio description.

A number of audiologists made submissions opposing the granting of the exemption. They note that watching captioned films is an important social activity for many of their clients. Several submissions also note that captions play an important role assisting some Deaf people, and particularly Deaf children, to develop their understanding of written English. Several of the submissions from audiologists note the prevalence of hearing loss in the Australian community and say that Australian society is ageing and that hearing loss is likely to become more common.

Several submissions contend that granting the exemption would be contrary to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) to which Australia is a signatory. These submissions note that article 30 (1)(b) of CRPD provides that States parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy access to films in accessible formats.

Some submissions note that Australia lags behind the rest of the world in the provision of captioning and audio description. Several submissions note that rates of captioning in the United Kingdom and the United States of America far exceed the rate at which captioning is available in Australia.

Applicant’s response to the submissions received by the Commission

In December 2009 the Commission wrote to the Applicantssummarising the submissions and inviting the Applicants to respond to the issues raised. The Applicants responded to the submissions received by the Commission in March 2010.

The Applicants state that some of the submissions appeared based on a misapprehension that the Applicants would remove the capacity to screen captioned films from the cinemas that are currently enabled to screen captioned films. The Applicants clarified that this was not what they proposed.

The Applicants note that the upgrade proposed in their application will cost more than $500,000.00. The Applicants state that this is about 5 times what they have spent on cinema captioning to date. The Applicants say that their proposal represents a substantial commitment to making cinema accessible.

The Applicants state that the advent of home theatre and legal and illegal downloading of films has placed them under pressure to maintain market share. They state that cinemas need to remain profitable to remain in business. They note that cinema sessions at which captioned films are shown are typically poorly attended and thus are not profitable to screen.

The Applicants note that introducing the technology to screen captioned and audio described films is one aspect of what is required to screen an accessible film. The other aspect is that distributors must provide the Applicants with films that have audio description and captions. The Applicants say that of the 346 films released in Australia last year, only 95 had captioning and only 59 had both captioning and audio description. The Applicants note the criticism that they screen few captioned or audio described ‘G’ rated films. The Applicants say that of the 95 captioned films released last year, 15 were suitable for families and 11 of those films were both captioned and audio described.

The Applicants advise that digital technology is coming to the cinema industry. They note that the technology required to screen captions on a digital film is not the same as the technology presently required to display captions on non-digital films. The Applicants say that their proposal would provide deaf and hearing impaired patrons with increased access to captioned films whilst allowing the Applicants to wait and see what changes digital technology may bring.

The Applicants note that the Commission has granted exemptions in relation to captioning in the past and refer to the exemptions granted to the free-to-air and subscription television providers.

In response to the claim that the Applicants are not providing captions and audio description at the same rate as cinema operators in other countries, the Applicants say that they are in a different position to operators in other countries. The Applicants say that cinemas in the United Kingdom receive a substantial amount of Government funding for the purchase of captioning and audio description technologies. The Applicants note that whilst the Australian Government provided some funding to independent cinemas in rural and regional areas, they have received no Government funding.

REASONS FOR DECISION

The Commission has considered all of the material that has been placed before it.

The Commission has decided to reject the application. The reasons for the Commission’s decision are as follows.

Insufficient reasons to support exemption

The Applicants have requested that the Commission grant the exemption in relation to cinema captioning and audio description so they can plan a coordinated rollout of captions across Australia rather than do so in response to individual complaints.

The Commission is not satisfied that responding to individual complaints of disability discrimination is such a burden on the Applicants that it should be considered to be a significant factor preventing the Applicants from proceeding with a coordinated rollout. The Applicants have not attempted to quantify the cost or time involved in responding to individual complaints.

Further, the Commission notes that if the Applicants implement a rollout across Australia of the technology to provide captioning and audio description that would be a significant factor in determining the issue of reasonableness and unjustifiable hardship in any discrimination claim. The Commission is therefore not satisfied that an exemption is required to achieve coordinated improvements in cinema access for hearing and vision impaired people.

Insufficient progress proposed

The Commission considers that the progress proposed by the Applicants as a condition to the exemption is insufficient to justify granting the exemption.

The Applicants propose that the Commission grant an exemption on condition that the Applicants would progressively rollout the technology necessary to screen captions and audio description. Under the Applicant’s proposal, at the conclusion of the exemption period a further 23 of the Applicants’ screens would be able to provide captions and audio description, taking the total number of the Applicants’ screens capable of displaying captions and audio description to 35 across Australia.

The Applicants operate 125 cinema complexes and 1182 cinemas screens across Australia. Under their proposal, the Applicants would make less than 30% of their cinema complexes and less than 3% of their screens accessible. Further, the Applicants propose to continue to screen one captioned film three times per week. Many submissions cited the statistic that providing captions at this rate means that 0.3% of the 40,000 films screened by the Applicants per week will be captioned. When viewed as a percentage of the service that Applicants provide, the number of locations and sessions at which the Applicants propose to provide captioning is unreasonably low.

The Applicants also propose that audio description would only be available at the three cinema sessions per week that are captioned. The Commission is of the view that this low rate of provision of audio description is inadequate. As audio description is a personal service delivered through headphones to the listener, it will not be heard by other cinema patrons. Once the technology is purchased for the screening of captioning and audio description, there is no reason why a cinema patron with a vision impairment should not be able to access any session of a film with audio description.

Currently 12 of the Applicants’ screens can provide captions and none can provide audio description. The Applicants propose to make a further 23 cinemas accessible over two and a half years. The Commission recognises that the proposal would nearly triple the number of cinemas which are currently accessible. The Commission also accepts that as the first accessible cinema was provided in 2001, the Applicants’ proposal would mean that more cinemas would be made accessible in the next two and a half years than has occurred in the previous nine years. However, the evidence before the Commission indicates that much greater progress can be made than is proposed.

In the Commission’s view, the limited rollout proposed by the Applicants is not justified when the cost of providing captions and audio descriptions is compared to the funds apparently available to the Applicants. The Applicants state the cost of installing the relevant technology in a further 23 cinemas to be $500,000. Spread across four large corporate entities this is not a significant sum of money. Publicly available information about the Applicants records a collective profit in the last financial year of hundreds of millions of dollars. Accordingly, it appears that the Applicants are able to undertake a more extensive rollout of captioning and audio description than they have proposed.

The Applicants suggest that their business is under threat from home cinema technology and film piracy. Whilst the Applicants’ business may be at some risk of reduced profits, the Applicants have provided no information to suggest that this threat is such that they are unable to afford the provision of captions and audio description at a rate higher than that proposed in their application.

The Applicants also suggest that the change to digital technology is imminent and this will alter the way that captioned and audio described films are screened. The Applicants have provided insufficient evidence to suggest that this change will occur so quickly that any funds spent on the existing technology for providing captioning would be wasted. If the technology for providing captioning does change within a short timeframe, the Commission is not satisfied that the Applicants will be unable to afford the purchase of the relevant new technology.

Detriment outweighs benefit

The DDA provides that services should be accessible to people with a disability. The CRPD provides that States parties should recognize the right of persons with disabilities to take part on an equal basis in cultural life, including in access to films. To grant an exemption that would limit the protection of these rights, the Commission takes the view that it should be satisfied that significant benefit will result.

Under the Applicants’ proposal, cinemas in some areas will not be made accessible for some time and cinemas in other areas will not be made accessible at all. However, if granted the exemption would affect the ability of all individuals to make complaints of disability discrimination against the Applicants about failure to provide captions and audio description. Thus significant numbers of people with a vision or hearing impairment will not have an accessible cinema in their neighbourhood and will not be able to complain about it.

The Commission considers that on balance any benefit in granting the exemption is outweighed by the detrimental effect on the right of people with a vision or hearing impairment to lodge complaints of disability discrimination in relation to cinema captioning.

Different to other captioning exemptions

The Applicants note that the Commission granted an exemption to the free to air and to subscription television providers in relation to the provision of captioning. However, the exemptions granted to the television providers involved conditions that they provide captions at a far higher level that that proposed by the Applicants. The exemption granted to the free to air television providers, for example, currently requires them to caption 80% of programs screened between 6 am and midnight by the end of 2010. The Applicants propose to provide access to less than 30% of their cinemas and less than 3% of their screens.

The Commission also notes that the exemption granted to the television providers had the same impact on all hearing impaired television viewers. All viewers had access to the same amount of captioned programs. In comparison, the limited rollout proposed by the Applicants means that in some areas of Australia, individuals will not gain access to captions and audio description and will have a limited ability to lodge a complaint about this. The Commission is of the view that there are substantial differences in the exemption proposed by the Applicants and that granted to the free-to-air television providers.

The Commission is conscious of the fact that Government is currently undertaking a review of media access in general, including cinema access, and encourages the Applicants to further consider how progress might be achieved in consultation with Government and organisations representing those seeking better access.

APPLICATION FOR REVIEW

Subject to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 (Cth), any person whose interests are affected by this decision many apply to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal for a review of the decision.

Dated this 29th day of April 2010.

Signed by the President, Catherine Branson QC