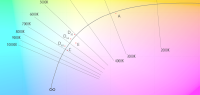

What they came up with is called the tri-stimulus system since the primary idea is that there are nerve endings in the eye which act as receptors, some of which primarily deal with green light, some with red and some with blue. These color receptors are called the cones (which don’t work at all in low light), while the receptors that can deal with low levels of light are called the rods.

Now, for the first of our amazing set of numbers, there are as many as 125 million receptors in the eye, of which only 6 or 7 million deal with color. When (predominantly) only one type of these receptors gets triggered, it will send a signal to the brain and the brain will designate the appropriate color. If two or more of these receptors are triggered, then the brain will do the work of combining them much the same way that a painter mixes water colors. (We’ll pretend it is that simple.)

OK; so how do you create a representation of all that color and detail on the TV or movie screen?

Let’s start with film. We think of it as one piece of plastic, but in reality it is several layers that each have a different dye of different sensitivity on it. Each dye reacts in a different and predictable manner when exposed to light through the camera lens. In the lab, each layer goes through a different chemical process to ‘develop’ a representation of what it captured when exposed by the camera system. There are a lot of steps in between, but eventually the film is exposed to light again, this time pushing light in the opposite manner, through the film and then through the lens. That light gets colored by the film and shows up on the screen.

One of the qualities of film is that the chemical and gel nature makes the range of colors in the image appear to be seamless. And not just ‘appears’ with the definition of “gives the impression of.” In fact, there is a great deal of resolution in modern film.

Then TV came along. We see a smooth piece of glass, but if we could touch the other side of a 1995 era TV set we would feel a dust that reacts to a strong beam of electricity. If we look real close we will see that there are actually different color dots, again green, red, and blue. Engineers figured out how to control that electric beam with magnets, which could trigger the different dots of color to make them light up separately or together to combine into a range of colors, and eventually combine those colors into pictures.

That was great, except people wanted better. Technology evolved to give them that. Instead of lighting up magic dust with a strong beam of electricity, a couple methods were discovered that allowed small colored capsules of gas to be lit up and even small pieces of colored plastic to light up. These segments and pieces were able to be packed tightly against each other so that they could make the pictures. Instead of only hundreds of lines being lit up by the electron gun in the old TV set, now over a thousand lines can be lit up, at higher speeds, using a lot less electricity.

Then a couple engineers figured out make and control a very tiny mirror to reflect light, then quickly move to not reflect light. That mirror is less than 25% of the size of a typical human hair.

Hundreds of these mirrors can be placed next to each other on a chip less than 2 centimeters square. Each mirror is able to precisely move on or off at a rate of 144 times a second, which is 6 times the speed that a motion picture film is exposed to light for a picture.

This chip is called a DLP, a Digital Light Projector, because a computer can tell each mirror when to turn one and off, so that when a strong light is reflected on an individual or set of mirrors, it will create part of a picture. If you put a computer in charge of 3 chips, one for green, one for red and one for blue, the reflected light can be focused through a lens and a very detailed picture will appear on the screen. There is a different but similar technology that Sony has refined for their professional cinema technology which uses crystals that change their state (status).

Now for the 2nd in our amazing set of numbers. There are 1,080 rows made up of 2,048 individual mirrors each for over 2 million 2 hundred thousand mirrors per chip. If you were to multiply that times 3 chips worth of mirrors, you get the same “about 6 or 7 million” mirrors as there are cones in each eye.

Without going into details (to keep this simple), we keep getting closer to being able to duplicate the range and intensity of colors that you see in the sky. This is one of the artists goals, in the same way as the engineers want to make a lighter, flatter, environmentally better television and movie playing system. It isn’t perfect, but picture quality has reached the point that incremental changes will be more subtle than substantive, or better only in larger rooms or specialist applications.

For example, a movie that uses the 2K standard will typically be in the 300 gigabyte size. A movie made in 4K, which technically has 4 times the resolution, will typically be less than 15% larger. This movie will be stored on a computer with many redundant drives, with redundant power supplies and graphics cards that are expressly made to be secure with special “digital cinema only” projectors.

Hopefully you have a feeling for the basic technology. It is not just being pushed onto people because it is the newest thing. The TV and movie businesses are going digital for a number of good reasons. To begin with, it wasn’t really possible to advance quality of the older technology without increasing the cost by a significant amount…and even then it would be incredibly cumbersome and remain an environmental nightmare. There are also advantages of flexibility that the new technology could do that the old couldn’t…or couldn’t at a reasonable price or at the quality of the new.

The technology of presenting a 3D image is one of those flexibility points. 3D was certainly one of the thrills of Avatar. The director worked for a decade learning how to handle the artistic and the technical sides of the art. He developed with closely aligned partners many different pieces of equipment and manners of using existing equipment to do things that haven’t been done before. And finally he spent hours on details that other budgets and people would only spend minutes. In the end James Cameron developed a technique and technology set that won’t be seen as normal for a long time from now…and an outstanding movie.

Could Avatar have been made on film? Well, almost no major motion picture has been made exclusively on film for a long time. They all use a technique named CGI (for the character generated imagery), which covers a grand set of techniques. But if you tried to generate the characters in Avatar exclusively on a computer with CGI, they never would have come out as detailed and inspiring as they did. Likewise, if he tried to create the characters with masks and other techniques with live action, you wouldn’t get the texture and feeling that the actors gave to their parts.

Could Avatar have been displayed with film, in 2D. Yes, it could have and it was.

3D is dealt with in more detail in Part II of this series, but here are some basics:

To begin, 3D is a misnomer. True 3 dimension presumes the ability to walk around a subject and see a full surround view, like the hologram of Princess Leah.

In real life a person who is partly hidden in one view, will be even more hidden or perhaps exposed from another view. On the screen of today’s 3D movie, when a character appears to b partly hidden by a wall as seen by a person on the left side of the theater, they will also appear the same amount of hidden by someone on the right side of the theater.

In fact, what we see with out eyes and what we see in the new theaters is correctly termed “stereoscopic”. We are taught some of this in school, how to make two lines join somewhere out in space (parallax) and draw all the boxes on those lines to make them appear to recede in the distance…even though they are on one piece of paper. There are several more clues in addition to parallax that we use to discern whether something is closer or farther, and whether something is just a drawing on a sheet of paper or a full rounded person or sharp-edged box…even in a 2D picture.

And we have been doing this for years. We know that Bogie and Bergman are in front of the plane that apparently sits in the distance…our eyes/brain/mind makes up a story for us, 3 dimensions and probably more, even though it is a black and white set of pictures shown at 24 frames per second on a flat screen.

Digital 3D is an imperfect feature as of now. It has improved enough that companies are investing a lot of money to make and show the movies. The technology will be improved as the artists learn the technology and what the audiences appreciate.

Although we are in a phase that seems like “All 3D, All The Time”, 3D isn’t the most important part of the digital cinema transition. At first blush the most important consideration is the savings from all the parts of movie distribution, including lower print costs and transportation costs. But actually, because prints no longer cost over a thousand euros, and because it will be simple to distribute a digital file, lesser known artists will have the opportunity to get their work in front of more people, and more people will find it easier to enjoy entertainment from other cultures and other parts of the world.

This Series now includes:

The State of Digital Cinema – April 2010 – Part 0

The State of Digital Cinema – April 2010 – Part I

The State of Digital Cinema – April 2010 – Part II

Ebert FUDs 3D and Digital Cinema