After many years of ![]() working on the issues at the UN level, then keeping the issues clarified for the different arms of the European Union structure, on 23 December 2010 the EU officially ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The EU is the first and only regional government body to accede to any international human rights treaty.

working on the issues at the UN level, then keeping the issues clarified for the different arms of the European Union structure, on 23 December 2010 the EU officially ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The EU is the first and only regional government body to accede to any international human rights treaty.

All EU countries have signed the documents, with only a handful who must still to ratify the treaty

, making the treaty binding law. By ratifying the treaty, countries pledge to uphold non-discrimination and other protections and to provide people with disabilities services they need to participate fully in society.

What does this mean? The European Disability Forum states:

All the institutions of the European Union will now have to endorse the values of the Convention in all policies under their competence ensuring mainstreaming of disability: from transport to employment and from information and communication technologies to development cooperation. It also means that they have to adjust the accessibility of their own buildings, their own employment and communications policy.

For example?

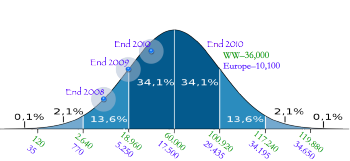

Recent statistics say that in the European Union, more than 80 million persons have a disability. This number is approximately 33% larger than the population of the UK, Italy, or France, or about equal to the population of Germany. It is 15% of the residents from all 27 EU countries. Again, from the EDF:

The Convention binds its States Parties to a revision of all existing legislation, policies and programs to ensure they are in compliance with its provisions. Concretely, it will mean actions in many areas such as access to education, employment, transport, infrastructures and buildings open to the public, granting right to vote and political participation, ensuring full legal capacity of all persons with disabilities, and a shift from institutions where persons with disabilities live separated from society into community and home-based services promoting independent living.

All the institutions of the European Union will now have to endorse the values of the Convention in all policies under their competence: from transport to employment and from information and communication technologies to development cooperation. It also means that they have to adjust the accessibility of their own buildings, their own employment and communications policy.

In human speak that means that each country is now charged with the requirement of reviewing, and changing where required, all laws, zoning codes, rights and privileges codes and any other mechanism that that might hamper the rights of persons with disabilities in all areas of life, or doesn’t advance those rights when required. The aim is for persons with disabilities to fully enjoy:

• Equal access and opportunities in education

• Equal access and treatment in employment

• Minimum income and social protection

• Equal opportunities in social protection, social security systems and social services, including personal assistance and personal budgets, when moving to another EU country

• Independent living and equal participation with the choice of social services of high quality

• Access to goods and services, transport and built environment

It is no small task to have gotten and kept the European Commission, the European Parliament, the European Council and all the 27 member states on the same agenda, signing onto a major piece of legislation less than 3 years after passage in the UN.

Meanwhile, the Digital Cinema world is over 10 years into the process of digitization, with approximately 33% of auditoriums converted from film-based equipment to digital media players and projectors. In some ways it is just leaving the science experiment stage. For example, almost

- 6 years after the March 2005 release of Version 1.0 of the DCI specification,

- 3+ years since the v 1.0 Digital Cinema Compliance Test Plan,

- 2 years since the majority of DCinema SMPTE Specifications became ISO documents,

— There are still no media servers through the test plan, and the first SMPTE Compliant movie packages (Digital Cinema Package – DCP) are hoped to be released in 3 months.

— Industry Plugfest tests, even one this year, have shown technical problems that prevent closed captions from consistently working with SMPTE or InterOp DCPs, even with the latest equipment and the latest software. Steady progress has been made, but results are still “uneven”.

This has left many people, companies and organizations frustrated. Many groups in the Deaf and Hard of Hearing communities took the promise given to them by experts, the technical explanations of what digital conversion would mean to them, and cooperated with studios and exhibitors in holding back their calls for specific equipment requirements. The logic was that the current analog equipment would be obsoleted soon, equipment which exhibitors could ill-afford while they were recovering from the overbuild and collapse of the industry in 2000/2001.

But digital cinema didn’t roll out as quickly as hoped, for many reasons. Manufacturers were kept busy during a transition from MPEG to the Motion JPEG format and several other major changes. Some failed and disappeared. New security mechanisms between the media player and projectors were put in place. There was, and continues to be, literally always something. And while the major Hollywood Studios were able to create their minimum standards documents (the DCI Specifications and Compliance Test Plans), the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE) took until 2008 to finish the majority of their detailed documents.

While their work continues, the finished documents were submitted and accepted by the ISO, the International Organization for Standardization. Countries like France (CNC document) and Germany have stated that these specifications and recommended practices would take the force of law.

The first major rollouts began in 2002 with the release of Star Wars II, but it took years to get to 1,000 installs, and it wasn’t until 2009 that the 10,000 number was reached. Large companies like Boeing and hard disk manufacturer Quantum got frustrated with the slow development of the industry and stopped their projects after spending millions. Likewise, the advocacy groups and the US Department of Justice restarted several lawsuits, and began another process that asked community participants to give their opinion on deadlines and solutions, the most recent being an Advance Notices of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRMs), one on the matter of Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability; Movie Captioning and Video Description – Department of Justice Request for Comments. Transcripts of hearings for these notices can be obtained here: Webcasts of Public Hearings on Advance Notices of Proposed Rulemakings(ANPRM).

In the US, it is 20 years since the Americans with Disability Act, and 10 years since the Department of Justice settled the assisted listening case (Crown Settlement re: Assistive Listening – 1991). There are further cases pending, the most watched being the Harkings case, and the most recent being a case from the Association of Late-Deafened Adults (ALDA) v Cinemark. Representatives of the Hearing Loss Association of America, the Harkings case, the National Association for the Deaf, NATO (National Association of Theater Owners, AMC Entertainment, and others can be found in the transcripts of the DoJ hearings. (Transcripts highlighted at places where the speaker discusses cinema issues here.)

As it stands now, the DoJ asked if 50% compliance in 5 years was reasonable, NATO responds that:

However, this is all so new that testing is still underway to ensure that everything works in a theater setting.

We need to know that the equipment is reliable, that movie goers can use the equipment, and we need to get hard numbers on what captioning and video description will cost.

We don’t have these answers. And we can’t answer the 90 questions that are before us. But we believe that these answers will be available within the next 24 months.

Somehow the advocacy groups for the hard of hearing didn’t find that 50% was in compliance with the language of 50 percent of the films shown would not result in “a full and equal enjoyment” as required by Title II of the ADA. One by one they insisted on 100%, and pushed the Overton window toward an insistence upon open caption for the 36 million deaf and hard of hearing Americans. Two clips from the testimonty:

…to provide captioning for no more than 50 percent of the films shown would not result in “full and equal enjoyment” required by title III of the ADA.

The Department notes the movie industry opposed any regulation that would require captioning. Had the movie industry moved ahead over the 20 years making movies fully accessible, we would not be sitting here today. We turn to the Department after years of frustration, years of waiting for captioning to be provided regularly by theaters anywhere, anytime, any screen.

— Hearing Loss Association of America

Our legal objection is that ADA clearly states that auxiliary aids and services like captioning are required unless the entity, singular and specific, the entity, can demonstrate that providing those aids and services would be an undue burden.

Because captioning is technically available, we think the undue burden inquiry is purely financial, and must be done on n individualized case by case basis, probably by a court. We don’t believe that substituting a broad performance-based standard which may ask too much of some but require too little of others, is consistent with a statutory undue burden standard. …

Regal, the nations largest theater chain, has informed us that essentially the incremental cost of captioning the second half of its 6800 theaters to show captioned movies would be about $3 million. That is big money, but put it in context. In 2009, according to publicly available documents, Regal paid over $110 million in dividends. Dividends. After the staff has been paid. After the leases have been paid. After the debt has been serviced. After you pay taxes on it. Dividends basically, according to some, are money that companies can’t figure out anything else to do with.

So they pay it in dividends. I would submit that 3 percent of your annual dividend cannot constitute an undue burden.

— John Waldo, attorney representing plaintiffs in ongoing movie captioning litigation in both Washington and California.

While the US experts have continued the adversarial tactic, cinema associations in England and Australia have settled their cases and worked along side the advocacy groups to bring more assistance to the hard of sight and hearing communities. Australia helped fund equipment in a rollout that is just beginning, while english cinemas have set up more open captioned and closed-captioned screenings and issues passes for people who assist the handicapped to get to the cinemas.

But much of the benefits still must wait until the rollout of SMPTE compliant DCinema Packages that begins in April 2011 and the equipment being developed and being released with that change.

One company in particular has been instrumental in pushing new ideas has been USL of California, introducing personal closed caption devices including glasses that float the words over the movie. Doremi has also introduced their CaptiView system, which has been used in the Australian rolll-out. Recently, Sony has announced a glasses based system.

Against this background, we introduce Mark Wheatley of the European Union of the Deaf. The EUD is a European non-profit organisation whose membership comprises National Associations of Deaf people in Europe. Established in 1985, EUD is the only organisation representing the interests of Deaf Europeans at European Union level. As part of our 3Questions Series, we ask him the following:

Q1) The European Union has now officially ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. How will this assist the needs of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community in the effort to participate – as it applies to cinemas – with:

Access to goods and services, transport and built environment

and

Equal access and treatment in employment

Article 30 – Participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sport

1. States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to take part on an equal basis with others in cultural life, and shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that persons with disabilities:

(c) Enjoy access to places for cultural performances or services, such as theatres, museums, cinemas, libraries and tourism services, and, as far as possible, enjoy access to monuments and sites of national cultural importance.

2. States Parties shall take appropriate measures to enable persons with disabilities to have the opportunity to develop and utilize their creative, artistic and intellectual potential, not only for their own benefit, but also for the enrichment of society.

The main issue deaf people face when going to the cinema is captioning to understand the communication on the screen but also the sounds (scary or ominous music or even setting the theme … Star Wars perhaps, Jaws even). For a number of European countries this is a none issue, when foreign films are shown, as they will often be captioned in the language of that country (I.e. A Japanese or Canadian film shown in Belgium, will more often than not, have captioning in French and Flemish) minus the scary music though.

Going to the cinema is something most people have done at some point in their life. People who do not rely on captioning really do take for granted the ease of being able to pick and choose the movie, time and location of what they wish to see, without any thought of needing to check if there will be captioning.

Many people have gone to the movies with family members when younger and with friends and partners when older. It is something most people have experienced in their life. What is sad is when hearing children have to interpret for their deaf parents in the sections where there is lots of dialogue (most movies), or parents with deaf children who choose a) not to take their deaf children to the movies because it is impossible to expect a child to focus for 1hour and half on a movie they do not understand or b) not go to the movies at all. Young people miss out on sharing popular and current cinema culture with their friends and families because the next captioned movie is not for many weeks or not being shown at all with captions.

People who are deaf do not wish to be marginalised by being offered screenings of movies (decided by others) or at times when nobody else wants to go to the cinema. Everyone wants to go to the cinema with friends or family at convenient times. We all expect freedom of choice, spontaneity, convenience and flexibility when we go to the cinema.

Article 27 – Work and employment

1. States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to work, on an equal basis with others; this includes the right to the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities. States Parties shall safeguard and promote the realization of the right to work, including for those who acquire a disability during the course of employment, by taking appropriate steps, including through legislation, to, inter alia: …

The area of cinematography and film making is vast and a large employer. There are many talented deaf film makers who now make films specifically for a deaf audience. While this is a band aid fix to a systematic flaw, it is hoped that in time cinemas will embrace a diversity of people within its staff and see how having people (such as Deaf individuals) can improve the overall service provided to the general public. Furthermore, many high school and university students have worked part time at their local cinema while making their way through school. I am not aware of any Deaf person who has ever worked in a cinema. That is not to say there have never been, but it does highlight how rare, even basic part time positions have not been made available for Deaf people.

Q2) It seems that cinemas in England have worked with various advocacy groups somewhat successfully and via their Cinema Exhibitors’ Association have implemented several programs and guidelines such as their document Best Practice Guidelines for the Provision of Services to Disabled Customer and Employment of Disabled People. We haven’t the impression that this is widespread throughout Europe though. How do you see this changing and what would be optimal from your viewpoint?

Mark WHEATLEY: Optimal would be people (read cinema managers) not thinking that they have to do things just for the sake of a guideline/law to allow a Deaf and hard of hearing people access to watch a popular movie now and then. Rather, by providing systematic access so that ANYONE can watch a movie. The family of 5 who have a Deaf child, means that for that whole family to watch and enjoy the movie, it needs to be captioned, even though captioning is technically for ONE person, the benefit would extend to 5 people, and 4 of them can hear.

It also means that people who are learning the language of that country would also come and pay to watch these movies.

Furthermore … the world population recently grew to 7 billion people. With people living longer, and many older people are losing their hearing and the current crop of Generation Y will lose their hearing earlier than any group before it, due to MP3 players and sub woofers in cars played at very high decibels, means that all these people will NEED captioned movies in the future to actually understand and enjoy the movies, not just Deaf people who communicate in sign language. By rolling out captioning across cinemas in Europe, it is not just best practice but ensuring cinemas houses will have people who will purchase tickets to watch movies in the future.

FYI, there is a very large group of people who do not purchase ANY TimeLife DVDs, as none of them come with captions, shameful considering the DVD collection is extensive that TimeLife release, and many are historic and related to past military battles, which mean many former soldiers who have lost their hearing in later life can not understand information about wars they actually fought in … its a travesty beyond words. Fortunately the BBC has an excellent collection, all with captions. This has garnered a large following of people who purchase their stock.

So providing captioning is not only a goodwill gesture to ensure accessibility, but it makes economic and business sense.

Q3) Is marketing and communication just as instrumental as technology and law, and how can your association assist with this element?

Mark WHEATLEY: EUD is working with the European Federation of Hard of Hearing People (EFHOH) and the European Association of Cochlear Implant Users (EURO-CIU) along with European Federation of Parents of Hearing Impaired Children (FEPEDA), to advance this very issue. EUD is meeting with these groups in the next few months to discuss campaign strategy.

Please contact EUD if you would like any further information.

Mark WHEATLEY

EUD Executive Director

European Union of the Deaf (EUD)

rue de la Loi – Wetstraat 26/15

B-1040 Brussels

BELGIUM

www.eud.eu