Stories don’t get better than this:

The Longest Shortest Double Bassist from NewYorker on Vimeo.

Stories don’t get better than this:

The Longest Shortest Double Bassist from NewYorker on Vimeo.

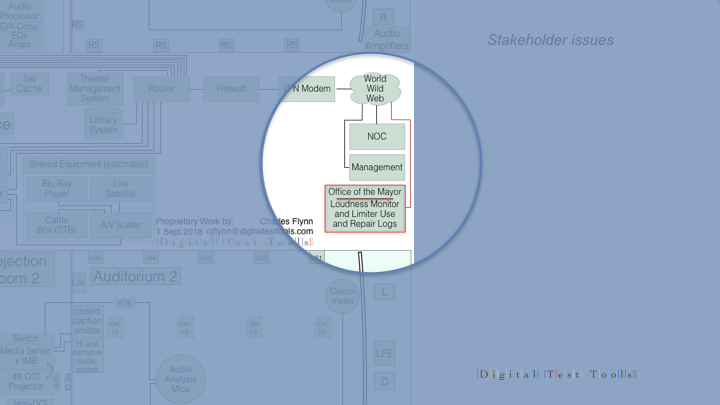

The takeaways are many. For the projection room it points to more vigilance – faster turnaround on software updates and a sharp eye for additional equipment tied into the network.

Read the whole thing and subscribe to his very readable newsletter at:

CRYPTO-GRAM

February 15, 2017

by Bruce Schneier

CTO, Resilient Systems, Inc.

[email protected]

https://www.schneier.com

A free monthly newsletter providing summaries, analyses, insights, and commentaries on security: computer and otherwise.

For back issues, or to subscribe, visit <https://www.schneier.com/crypto-gram.html>.

You can read this issue on the web at <https://www.schneier.com/crypto-gram/archives/2017/0215.html>. These same essays and news items appear in the “Schneier on Security” blog at <http://www.schneier.com/blog>, along with a lively and intelligent comment section. An RSS feed is available.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

In this issue:

Security and the Internet of Things

News

Schneier News

Security and Privacy Guidelines for the Internet of Things

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Security and the Internet of Things

Last year, on October 21, your digital video recorder — or at least a DVR like yours — knocked Twitter off the Internet. Someone used your DVR, along with millions of insecure webcams, routers, and other connected devices, to launch an attack that started a chain reaction, resulting in Twitter, Reddit, Netflix, and many sites going off the Internet. You probably didn’t realize that your DVR had that kind of power. But it does.

All computers are hackable. This has as much to do with the computer market as it does with the technologies. We prefer our software full of features and inexpensive, at the expense of security and reliability. That your computer can affect the security of Twitter is a market failure. The industry is filled with market failures that, until now, have been largely ignorable. As computers continue to permeate our homes, cars, businesses, these market failures will no longer be tolerable. Our only solution will be regulation, and that regulation will be foisted on us by a government desperate to “do something” in the face of disaster.

In this article I want to outline the problems, both technical and political, and point to some regulatory solutions. “Regulation” might be a dirty word in today’s political climate, but security is the exception to our small-government bias. And as the threats posed by computers become greater and more catastrophic, regulation will be inevitable. So now’s the time to start thinking about it.

We also need to reverse the trend to connect everything to the Internet. And if we risk harm and even death, we need to think twice about what we connect and what we deliberately leave uncomputerized.

If we get this wrong, the computer industry will look like the pharmaceutical industry, or the aircraft industry. But if we get this right, we can maintain the innovative environment of the Internet that has given us so much.

—– —–

We no longer have things with computers embedded in them. We have computers with things attached to them.

Your modern refrigerator is a computer that keeps things cold. Your oven, similarly, is a computer that makes things hot. An ATM is a computer with money inside. Your car is no longer a mechanical device with some computers inside; it’s a computer with four wheels and an engine. Actually, it’s a distributed system of over 100 computers with four wheels and an engine. And, of course, your phones became full-power general-purpose computers in 2007, when the iPhone was introduced.

We wear computers: fitness trackers and computer-enabled medical devices — and, of course, we carry our smartphones everywhere. Our homes have smart thermostats, smart appliances, smart door locks, even smart light bulbs. At work, many of those same smart devices are networked together with CCTV cameras, sensors that detect customer movements, and everything else. Cities are starting to embed smart sensors in roads, streetlights, and sidewalk squares, also smart energy grids and smart transportation networks. A nuclear power plant is really just a computer that produces electricity, and — like everything else we’ve just listed — it’s on the Internet.

The Internet is no longer a web that we connect to. Instead, it’s a computerized, networked, and interconnected world that we live in. This is the future, and what we’re calling the Internet of Things.

Broadly speaking, the Internet of Things has three parts. There are the sensors that collect data about us and our environment: smart thermostats, street and highway sensors, and those ubiquitous smartphones with their motion sensors and GPS location receivers. Then there are the “smarts” that figure out what the data means and what to do about it. This includes all the computer processors on these devices and — increasingly — in the cloud, as well as the memory that stores all of this information. And finally, there are the actuators that affect our environment. The point of a smart thermostat isn’t to record the temperature; it’s to control the furnace and the air conditioner. Driverless cars collect data about the road and the environment to steer themselves safely to their destinations.

You can think of the sensors as the eyes and ears of the Internet. You can think of the actuators as the hands and feet of the Internet. And you can think of the stuff in the middle as the brain. We are building an Internet that senses, thinks, and acts.

This is the classic definition of a robot. We’re building a world-size robot, and we don’t even realize it.

To be sure, it’s not a robot in the classical sense. We think of robots as discrete autonomous entities, with sensors, brain, and actuators all together in a metal shell. The world-size robot is distributed. It doesn’t have a singular body, and parts of it are controlled in different ways by different people. It doesn’t have a central brain, and it has nothing even remotely resembling a consciousness. It doesn’t have a single goal or focus. It’s not even something we deliberately designed. It’s something we have inadvertently built out of the everyday objects we live with and take for granted. It is the extension of our computers and networks into the real world.

This world-size robot is actually more than the Internet of Things. It’s a combination of several decades-old computing trends: mobile computing, cloud computing, always-on computing, huge databases of personal information, the Internet of Things — or, more precisely, cyber-physical systems — autonomy, and artificial intelligence. And while it’s still not very smart, it’ll get smarter. It’ll get more powerful and more capable through all the interconnections we’re building.

It’ll also get much more dangerous.

—– —–

Computer security has been around for almost as long as computers have been. And while it’s true that security wasn’t part of the design of the original Internet, it’s something we have been trying to achieve since its beginning.

I have been working in computer security for over 30 years: first in cryptography, then more generally in computer and network security, and now in general security technology. I have watched computers become ubiquitous, and have seen firsthand the problems — and solutions — of securing these complex machines and systems. I’m telling you all this because what used to be a specialized area of expertise now affects everything. Computer security is now everything security. There’s one critical difference, though: The threats have become greater.

Traditionally, computer security is divided into three categories: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. For the most part, our security concerns have largely centered around confidentiality. We’re concerned about our data and who has access to it — the world of privacy and surveillance, of data theft and misuse.

But threats come in many forms. Availability threats: computer viruses that delete our data, or ransomware that encrypts our data and demands payment for the unlock key. Integrity threats: hackers who can manipulate data entries can do things ranging from changing grades in a class to changing the amount of money in bank accounts. Some of these threats are pretty bad. Hospitals have paid tens of thousands of dollars to criminals whose ransomware encrypted critical medical files. JPMorgan Chase spends half a billion on cybersecurity a year.

Today, the integrity and availability threats are much worse than the confidentiality threats. Once computers start affecting the world in a direct and physical manner, there are real risks to life and property. There is a fundamental difference between crashing your computer and losing your spreadsheet data, and crashing your pacemaker and losing your life. This isn’t hyperbole; recently researchers found serious security vulnerabilities in St. Jude Medical’s implantable heart devices. Give the Internet hands and feet, and it will have the ability to punch and kick.

Take a concrete example: modern cars, those computers on wheels. The steering wheel no longer turns the axles, nor does the accelerator pedal change the speed. Every move you make in a car is processed by a computer, which does the actual controlling. A central computer controls the dashboard. There’s another in the radio. The engine has 20 or so computers. These are all networked, and increasingly autonomous.

Now, let’s start listing the security threats. We don’t want car navigation systems to be used for mass surveillance, or the microphone for mass eavesdropping. We might want it to be used to determine a car’s location in the event of a 911 call, and possibly to collect information about highway congestion. We don’t want people to hack their own cars to bypass emissions-control limitations. We don’t want manufacturers or dealers to be able to do that, either, as Volkswagen did for years. We can imagine wanting to give police the ability to remotely and safely disable a moving car; that would make high-speed chases a thing of the past. But we definitely don’t want hackers to be able to do that. We definitely don’t want them disabling the brakes in every car without warning, at speed. As we make the transition from driver-controlled cars to cars with various driver-assist capabilities to fully driverless cars, we don’t want any of those critical components subverted. We don’t want someone to be able to accidentally crash your car, let alone do it on purpose. And equally, we don’t want them to be able to manipulate the navigation software to change your route, or the door-lock controls to prevent you from opening the door. I could go on.

That’s a lot of different security requirements, and the effects of getting them wrong range from illegal surveillance to extortion by ransomware to mass death.

—– —–

Our computers and smartphones are as secure as they are because companies like Microsoft, Apple, and Google spend a lot of time testing their code before it’s released, and quickly patch vulnerabilities when they’re discovered. Those companies can support large, dedicated teams because those companies make a huge amount of money, either directly or indirectly, from their software — and, in part, compete on its security. Unfortunately, this isn’t true of embedded systems like digital video recorders or home routers. Those systems are sold at a much lower margin, and are often built by offshore third parties. The companies involved simply don’t have the expertise to make them secure.

At a recent hacker conference, a security researcher analyzed 30 home routers and was able to break into half of them, including some of the most popular and common brands. The denial-of-service attacks that forced popular websites like Reddit and Twitter off the Internet last October were enabled by vulnerabilities in devices like webcams and digital video recorders. In August, two security researchers demonstrated a ransomware attack on a smart thermostat.

Even worse, most of these devices don’t have any way to be patched. Companies like Microsoft and Apple continuously deliver security patches to your computers. Some home routers are technically patchable, but in a complicated way that only an expert would attempt. And the only way for you to update the firmware in your hackable DVR is to throw it away and buy a new one.

The market can’t fix this because neither the buyer nor the seller cares. The owners of the webcams and DVRs used in the denial-of-service attacks don’t care. Their devices were cheap to buy, they still work, and they don’t know any of the victims of the attacks. The sellers of those devices don’t care: They’re now selling newer and better models, and the original buyers only cared about price and features. There is no market solution, because the insecurity is what economists call an externality: It’s an effect of the purchasing decision that affects other people. Think of it kind of like invisible pollution.

—– —–

Security is an arms race between attacker and defender. Technology perturbs that arms race by changing the balance between attacker and defender. Understanding how this arms race has unfolded on the Internet is essential to understanding why the world-size robot we’re building is so insecure, and how we might secure it. To that end, I have five truisms, born from what we’ve already learned about computer and Internet security. They will soon affect the security arms race everywhere.

Truism No. 1: On the Internet, attack is easier than defense.

There are many reasons for this, but the most important is the complexity of these systems. More complexity means more people involved, more parts, more interactions, more mistakes in the design and development process, more of everything where hidden insecurities can be found. Computer-security experts like to speak about the attack surface of a system: all the possible points an attacker might target and that must be secured. A complex system means a large attack surface. The defender has to secure the entire attack surface. The attacker just has to find one vulnerability — one unsecured avenue for attack — and gets to choose how and when to attack. It’s simply not a fair battle.

There are other, more general, reasons why attack is easier than defense. Attackers have a natural agility that defenders often lack. They don’t have to worry about laws, and often not about morals or ethics. They don’t have a bureaucracy to contend with, and can more quickly make use of technical innovations. Attackers also have a first-mover advantage. As a society, we’re generally terrible at proactive security; we rarely take preventive security measures until an attack actually happens. So more advantages go to the attacker.

Truism No. 2: Most software is poorly written and insecure.

If complexity isn’t enough, we compound the problem by producing lousy software. Well-written software, like the kind found in airplane avionics, is both expensive and time-consuming to produce. We don’t want that. For the most part, poorly written software has been good enough. We’d all rather live with buggy software than pay the prices good software would require. We don’t mind if our games crash regularly, or our business applications act weird once in a while. Because software has been largely benign, it hasn’t mattered. This has permeated the industry at all levels. At universities, we don’t teach how to code well. Companies don’t reward quality code in the same way they reward fast and cheap. And we consumers don’t demand it.

But poorly written software is riddled with bugs, sometimes as many as one per 1,000 lines of code. Some of them are inherent in the complexity of the software, but most are programming mistakes. Not all bugs are vulnerabilities, but some are.

Truism No. 3: Connecting everything to each other via the Internet will expose new vulnerabilities.

The more we network things together, the more vulnerabilities on one thing will affect other things. On October 21, vulnerabilities in a wide variety of embedded devices were all harnessed together to create what hackers call a botnet. This botnet was used to launch a distributed denial-of-service attack against a company called Dyn. Dyn provided a critical Internet function for many major Internet sites. So when Dyn went down, so did all those popular websites.

These chains of vulnerabilities are everywhere. In 2012, journalist Mat Honan suffered a massive personal hack because of one of them. A vulnerability in his Amazon account allowed hackers to get into his Apple account, which allowed them to get into his Gmail account. And in 2013, the Target Corporation was hacked by someone stealing credentials from its HVAC contractor.

Vulnerabilities like these are particularly hard to fix, because no one system might actually be at fault. It might be the insecure interaction of two individually secure systems.

Truism No. 4: Everybody has to stop the best attackers in the world.

One of the most powerful properties of the Internet is that it allows things to scale. This is true for our ability to access data or control systems or do any of the cool things we use the Internet for, but it’s also true for attacks. In general, fewer attackers can do more damage because of better technology. It’s not just that these modern attackers are more efficient, it’s that the Internet allows attacks to scale to a degree impossible without computers and networks.

This is fundamentally different from what we’re used to. When securing my home against burglars, I am only worried about the burglars who live close enough to my home to consider robbing me. The Internet is different. When I think about the security of my network, I have to be concerned about the best attacker possible, because he’s the one who’s going to create the attack tool that everyone else will use. The attacker that discovered the vulnerability used to attack Dyn released the code to the world, and within a week there were a dozen attack tools using it.

Truism No. 5: Laws inhibit security research.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act is a terrible law that fails at its purpose of preventing widespread piracy of movies and music. To make matters worse, it contains a provision that has critical side effects. According to the law, it is a crime to bypass security mechanisms that protect copyrighted work, even if that bypassing would otherwise be legal. Since all software can be copyrighted, it is arguably illegal to do security research on these devices and to publish the result.

Although the exact contours of the law are arguable, many companies are using this provision of the DMCA to threaten researchers who expose vulnerabilities in their embedded systems. This instills fear in researchers, and has a chilling effect on research, which means two things: (1) Vendors of these devices are more likely to leave them insecure, because no one will notice and they won’t be penalized in the market, and (2) security engineers don’t learn how to do security better.

Unfortunately, companies generally like the DMCA. The provisions against reverse-engineering spare them the embarrassment of having their shoddy security exposed. It also allows them to build proprietary systems that lock out competition. (This is an important one. Right now, your toaster cannot force you to only buy a particular brand of bread. But because of this law and an embedded computer, your Keurig coffee maker can force you to buy a particular brand of coffee.)

—– —–

In general, there are two basic paradigms of security. We can either try to secure something well the first time, or we can make our security agile. The first paradigm comes from the world of dangerous things: from planes, medical devices, buildings. It’s the paradigm that gives us secure design and secure engineering, security testing and certifications, professional licensing, detailed preplanning and complex government approvals, and long times-to-market. It’s security for a world where getting it right is paramount because getting it wrong means people dying.

The second paradigm comes from the fast-moving and heretofore largely benign world of software. In this paradigm, we have rapid prototyping, on-the-fly updates, and continual improvement. In this paradigm, new vulnerabilities are discovered all the time and security disasters regularly happen. Here, we stress survivability, recoverability, mitigation, adaptability, and muddling through. This is security for a world where getting it wrong is okay, as long as you can respond fast enough.

These two worlds are colliding. They’re colliding in our cars — literally — in our medical devices, our building control systems, our traffic control systems, and our voting machines. And although these paradigms are wildly different and largely incompatible, we need to figure out how to make them work together.

So far, we haven’t done very well. We still largely rely on the first paradigm for the dangerous computers in cars, airplanes, and medical devices. As a result, there are medical systems that can’t have security patches installed because that would invalidate their government approval. In 2015, Chrysler recalled 1.4 million cars to fix a software vulnerability. In September 2016, Tesla remotely sent a security patch to all of its Model S cars overnight. Tesla sure sounds like it’s doing things right, but what vulnerabilities does this remote patch feature open up?

—– —–

Until now we’ve largely left computer security to the market. Because the computer and network products we buy and use are so lousy, an enormous after-market industry in computer security has emerged. Governments, companies, and people buy the security they think they need to secure themselves. We’ve muddled through well enough, but the market failures inherent in trying to secure this world-size robot will soon become too big to ignore.

Markets alone can’t solve our security problems. Markets are motivated by profit and short-term goals at the expense of society. They can’t solve collective-action problems. They won’t be able to deal with economic externalities, like the vulnerabilities in DVRs that resulted in Twitter going offline. And we need a counterbalancing force to corporate power.

This all points to policy. While the details of any computer-security system are technical, getting the technologies broadly deployed is a problem that spans law, economics, psychology, and sociology. And getting the policy right is just as important as getting the technology right because, for Internet security to work, law and technology have to work together. This is probably the most important lesson of Edward Snowden’s NSA disclosures. We already knew that technology can subvert law. Snowden demonstrated that law can also subvert technology. Both fail unless each work. It’s not enough to just let technology do its thing.

Any policy changes to secure this world-size robot will mean significant government regulation. I know it’s a sullied concept in today’s world, but I don’t see any other possible solution. It’s going to be especially difficult on the Internet, where its permissionless nature is one of the best things about it and the underpinning of its most world-changing innovations. But I don’t see how that can continue when the Internet can affect the world in a direct and physical manner.

—– —–

I have a proposal: a new government regulatory agency. Before dismissing it out of hand, please hear me out.

We have a practical problem when it comes to Internet regulation. There’s no government structure to tackle this at a systemic level. Instead, there’s a fundamental mismatch between the way government works and the way this technology works that makes dealing with this problem impossible at the moment.

Government operates in silos. In the U.S., the FAA regulates aircraft. The NHTSA regulates cars. The FDA regulates medical devices. The FCC regulates communications devices. The FTC protects consumers in the face of “unfair” or “deceptive” trade practices. Even worse, who regulates data can depend on how it is used. If data is used to influence a voter, it’s the Federal Election Commission’s jurisdiction. If that same data is used to influence a consumer, it’s the FTC’s. Use those same technologies in a school, and the Department of Education is now in charge. Robotics will have its own set of problems, and no one is sure how that is going to be regulated. Each agency has a different approach and different rules. They have no expertise in these new issues, and they are not quick to expand their authority for all sorts of reasons.

Compare that with the Internet. The Internet is a freewheeling system of integrated objects and networks. It grows horizontally, demolishing old technological barriers so that people and systems that never previously communicated now can. Already, apps on a smartphone can log health information, control your energy use, and communicate with your car. That’s a set of functions that crosses jurisdictions of at least four different government agencies, and it’s only going to get worse.

Our world-size robot needs to be viewed as a single entity with millions of components interacting with each other. Any solutions here need to be holistic. They need to work everywhere, for everything. Whether we’re talking about cars, drones, or phones, they’re all computers.

This has lots of precedent. Many new technologies have led to the formation of new government regulatory agencies. Trains did, cars did, airplanes did. Radio led to the formation of the Federal Radio Commission, which became the FCC. Nuclear power led to the formation of the Atomic Energy Commission, which eventually became the Department of Energy. The reasons were the same in every case. New technologies need new expertise because they bring with them new challenges. Governments need a single agency to house that new expertise, because its applications cut across several preexisting agencies. It’s less that the new agency needs to regulate — although that’s often a big part of it — and more that governments recognize the importance of the new technologies.

The Internet has famously eschewed formal regulation, instead adopting a multi-stakeholder model of academics, businesses, governments, and other interested parties. My hope is that we can keep the best of this approach in any regulatory agency, looking more at the new U.S. Digital Service or the 18F office inside the General Services Administration. Both of those organizations are dedicated to providing digital government services, and both have collected significant expertise by bringing people in from outside of government, and both have learned how to work closely with existing agencies. Any Internet regulatory agency will similarly need to engage in a high level of collaborate regulation — both a challenge and an opportunity.

I don’t think any of us can predict the totality of the regulations we need to ensure the safety of this world, but here’s a few. We need government to ensure companies follow good security practices: testing, patching, secure defaults — and we need to be able to hold companies liable when they fail to do these things. We need government to mandate strong personal data protections, and limitations on data collection and use. We need to ensure that responsible security research is legal and well-funded. We need to enforce transparency in design, some sort of code escrow in case a company goes out of business, and interoperability between devices of different manufacturers, to counterbalance the monopolistic effects of interconnected technologies. Individuals need the right to take their data with them. And Internet-enabled devices should retain some minimal functionality if disconnected from the Internet.

I’m not the only one talking about this. I’ve seen proposals for a National Institutes of Health analogue for cybersecurity. University of Washington law professor Ryan Calo has proposed a Federal Robotics Commission. I think it needs to be broader: maybe a Department of Technology Policy.

Of course there will be problems. There’s a lack of expertise in these issues inside government. There’s a lack of willingness in government to do the hard regulatory work. Industry is worried about any new bureaucracy: both that it will stifle innovation by regulating too much and that it will be captured by industry and regulate too little. A domestic regulatory agency will have to deal with the fundamentally international nature of the problem.

But government is the entity we use to solve problems like this. Governments have the scope, scale, and balance of interests to address the problems. It’s the institution we’ve built to adjudicate competing social interests and internalize market externalities. Left to their own devices, the market simply can’t. That we’re currently in the middle of an era of low government trust, where many of us can’t imagine government doing anything positive in an area like this, is to our detriment.

Here’s the thing: Governments will get involved, regardless. The risks are too great, and the stakes are too high. Government already regulates dangerous physical systems like cars and medical devices. And nothing motivates the U.S. government like fear. Remember 2001? A nominally small-government Republican president created the Office of Homeland Security 11 days after the terrorist attacks: a rushed and ill-thought-out decision that we’ve been trying to fix for over a decade. A fatal disaster will similarly spur our government into action, and it’s unlikely to be well-considered and thoughtful action. Our choice isn’t between government involvement and no government involvement. Our choice is between smarter government involvement and stupider government involvement. We have to start thinking about this now. Regulations are necessary, important, and complex; and they’re coming. We can’t afford to ignore these issues until it’s too late.

We also need to start disconnecting systems. If we cannot secure complex systems to the level required by their real-world capabilities, then we must not build a world where everything is computerized and interconnected.

There are other models. We can enable local communications only. We can set limits on collected and stored data. We can deliberately design systems that don’t interoperate with each other. We can deliberately fetter devices, reversing the current trend of turning everything into a general-purpose computer. And, most important, we can move toward less centralization and more distributed systems, which is how the Internet was first envisioned.

This might be a heresy in today’s race to network everything, but large, centralized systems are not inevitable. The technical elites are pushing us in that direction, but they really don’t have any good supporting arguments other than the profits of their ever-growing multinational corporations.

But this will change. It will change not only because of security concerns, it will also change because of political concerns. We’re starting to chafe under the worldview of everything producing data about us and what we do, and that data being available to both governments and corporations. Surveillance capitalism won’t be the business model of the Internet forever. We need to change the fabric of the Internet so that evil governments don’t have the tools to create a horrific totalitarian state. And while good laws and regulations in Western democracies are a great second line of defense, they can’t be our only line of defense.

My guess is that we will soon reach a high-water mark of computerization and connectivity, and that afterward we will make conscious decisions about what and how we decide to interconnect. But we’re still in the honeymoon phase of connectivity. Governments and corporations are punch-drunk on our data, and the rush to connect everything is driven by an even greater desire for power and market share. One of the presentations released by Edward Snowden contained the NSA mantra: “Collect it all.” A similar mantra for the Internet today might be: “Connect it all.”

The inevitable backlash will not be driven by the market. It will be deliberate policy decisions that put the safety and welfare of society above individual corporations and industries. It will be deliberate policy decisions that prioritize the security of our systems over the demands of the FBI to weaken them in order to make their law-enforcement jobs easier. It’ll be hard policy for many to swallow, but our safety will depend on it.

—– —–

The scenarios I’ve outlined, both the technological and economic trends that are causing them and the political changes we need to make to start to fix them, come from my years of working in Internet-security technology and policy. All of this is informed by an understanding of both technology and policy. That turns out to be critical, and there aren’t enough people who understand both.

This brings me to my final plea: We need more public-interest technologists.

Over the past couple of decades, we’ve seen examples of getting Internet-security policy badly wrong. I’m thinking of the FBI’s “going dark” debate about its insistence that computer devices be designed to facilitate government access, the “vulnerability equities process” about when the government should disclose and fix a vulnerability versus when it should use it to attack other systems, the debacle over paperless touch-screen voting machines, and the DMCA that I discussed above. If you watched any of these policy debates unfold, you saw policy-makers and technologists talking past each other.

Our world-size robot will exacerbate these problems. The historical divide between Washington and Silicon Valley — the mistrust of governments by tech companies and the mistrust of tech companies by governments — is dangerous.

We have to fix this. Getting IoT security right depends on the two sides working together and, even more important, having people who are experts in each working on both. We need technologists to get involved in policy, and we need policy-makers to get involved in technology. We need people who are experts in making both technology and technological policy. We need technologists on congressional staffs, inside federal agencies, working for NGOs, and as part of the press. We need to create a viable career path for public-interest technologists, much as there already is one for public-interest attorneys. We need courses, and degree programs in colleges, for people interested in careers in public-interest technology. We need fellowships in organizations that need these people. We need technology companies to offer sabbaticals for technologists wanting to go down this path. We need an entire ecosystem that supports people bridging the gap between technology and law. We need a viable career path that ensures that even though people in this field won’t make as much as they would in a high-tech start-up, they will have viable careers. The security of our computerized and networked future — meaning the security of ourselves, families, homes, businesses, and communities — depends on it.

This plea is bigger than security, actually. Pretty much all of the major policy debates of this century will have a major technological component. Whether it’s weapons of mass destruction, robots drastically affecting employment, climate change, food safety, or the increasing ubiquity of ever-shrinking drones, understanding the policy means understanding the technology. Our society desperately needs technologists working on the policy. The alternative is bad policy.

—– —–

The world-size robot is less designed than created. It’s coming without any forethought or architecting or planning; most of us are completely unaware of what we’re building. In fact, I am not convinced we can actually design any of this. When we try to design complex sociotechnical systems like this, we are regularly surprised by their emergent properties. The best we can do is observe and channel these properties as best we can.

Market thinking sometimes makes us lose sight of the human choices and autonomy at stake. Before we get controlled — or killed — by the world-size robot, we need to rebuild confidence in our collective governance institutions. Law and policy may not seem as cool as digital tech, but they’re also places of critical innovation. They’re where we collectively bring about the world we want to live in.

While I might sound like a Cassandra, I’m actually optimistic about our future. Our society has tackled bigger problems than this one. It takes work and it’s not easy, but we eventually find our way clear to make the hard choices necessary to solve our real problems.

The world-size robot we’re building can only be managed responsibly if we start making real choices about the interconnected world we live in. Yes, we need security systems as robust as the threat landscape. But we also need laws that effectively regulate these dangerous technologies. And, more generally, we need to make moral, ethical, and political decisions on how those systems should work. Until now, we’ve largely left the Internet alone. We gave programmers a special right to code cyberspace as they saw fit. This was okay because cyberspace was separate and relatively unimportant: That is, it didn’t matter. Now that that’s changed, we can no longer give programmers and the companies they work for this power. Those moral, ethical, and political decisions need, somehow, to be made by everybody. We need to link people with the same zeal that we are currently linking machines. “Connect it all” must be countered with “connect us all.”

This essay previously appeared in “New York Magazine.”

http://nymag.com/selectall/2017/01/the-Internet-of-things-dangerous-future-bruce-schneier.html

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

News

Interesting post on Cloudflare’s experience with receiving a National Security Letter.

https://blog.cloudflare.com/cloudflares-transparency-report-for-second-half-2016-and-an-additional-disclosure-for-2013-2/

News article.

https://techcrunch.com/2017/01/11/cloudflare-explains-how-fbi-gag-order-impacted-business/

Complicated reporting on a WhatsApp security vulnerability, which is more of a design decision than an actual vulnerability.

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2017/01/whatsapp_securi.html

Be sure to read Zeynep Tufekci’s letter to the Guardian, which I also signed.

http://technosociology.org/?page_id=1687

Brian Krebs uncovers the Mirai botnet author.

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2017/01/who-is-anna-senpai-the-mirai-worm-author/#more-37412

There’s research in using a heartbeat as a biometric password. No details in the article. My guess is that there isn’t nearly enough entropy in the reproducible biometric, but I might be surprised. The article’s suggestion to use it as a password for health records seems especially problematic. “I’m sorry, but we can’t access the patient’s health records because he’s having a heart attack.”

https://www.ecnmag.com/news/2017/01/heartbeat-could-be-used-password-access-electronic-health-records

I wrote about this before here.

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2015/08/heartbeat_as_a_.html

In early January, the Obama White House released a report on privacy: “Privacy in our Digital Lives: Protecting Individuals and Promoting Innovation.” The report summarizes things the administration has done, and lists future challenges. It’s worth reading. I especially like the framing of privacy as a right. From President Obama’s introduction. The document was originally on the whitehouse.gov website, but was deleted in the Trump transition.

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2017/01/new_white_house.html

https://www.schneier.com/blog/files/Privacy_in_Our_Digital_Lives.pdf

NextGov has a nice article summarizing President Obama’s accomplishments in Internet security: what he did, what he didn’t do, and how it turned out.

http://www.nextgov.com/cybersecurity/2017/01/obamas-cyber-legacy-he-did-almost-everything-right-and-it-still-turned-out-wrong/134612/

Good article that crunches the data and shows that the press’s coverage of terrorism is disproportional to its comparative risk.

https://priceonomics.com/our-fixation-on-terrorism

This isn’t new. I’ve written about it before, and wrote about it more generally when I wrote about the psychology of risk, fear, and security. Basically, the issue is the availability heuristic. We tend to infer the probability of something by how easy it is to bring examples of the thing to mind. So if we can think of a lot of tiger attacks in our community, we infer that the risk is high. If we can’t think of many lion attacks, we infer that the risk is low. But while this is a perfectly reasonable heuristic when living in small family groups in the East African highlands in 100,000 BC, it fails in the face of modern media. The media makes the rare seem more common by spending a lot of time talking about it. It’s not the media’s fault. By definition, news is “something that hardly ever happens.” But when the coverage of terrorist deaths exceeds the coverage of homicides, we have a tendency to mistakenly inflate the risk of the former while discount the risk of the latter.

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2007/05/rare_risk_and_o_1.html

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2009/03/fear_and_the_av.html

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2007/05/rare_risk_and_o_1.html

https://www.schneier.com/essays/archives/2008/01/the_psychology_of_se.html

Interesting research on cracking the Android pattern-lock authentication system with a computer vision algorithm that tracks fingertip movements.

http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/wangz3/publications/ndss_17.pdf

https://phys.org/news/2017-01-android-device-pattern.html

Reports are that President Trump is still using his old Android phone. There are security risks here, but they are not the obvious ones. I’m not concerned about the data. Anything he reads on that screen is coming from the insecure network that we all use, and any e-mails, texts, Tweets, and whatever are going out to that same network. But this is a consumer device, and it’s going to have security vulnerabilities. He’s at risk from everybody, ranging from lone hackers to the better-funded intelligence agencies of the world. And while the risk of a forged e-mail is real — it could easily move the stock market — the bigger risk is eavesdropping. That Android has a microphone, which means that it can be turned into a room bug without anyone’s knowledge. That’s my real fear.

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/01/post-inauguration-president-trump-still-uses-his-old-android-phone/

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/25/us/politics/president-trump-white-house.html

https://www.wired.com/2017/01/trump-android-phone-security-threat/

http://www.politico.com/tipsheets/morning-cybersecurity/2017/01/the-changing-face-of-cyber-espionage-218420

https://www.lawfareblog.com/president-trumps-insecure-android

Mike Specter has an interesting idea on how to make biometric access-control systems more secure: add a duress code. For example, you might configure your iPhone so that either thumb or forefinger unlocks the device, but your left middle finger disables the fingerprint mechanism (useful in the US where being compelled to divulge your password is a 5th Amendment violation but being forced to place your finger on the fingerprint reader is not) and the right middle finger permanently wipes the phone (useful in other countries where coercion techniques are much more severe).

http://www.mit.edu/~specter/articles/17/deniability1.html

Research into Twitter bots. It turns out that there are a lot of them.

http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-38724082

In a world where the number of fans, friends, followers, and likers are social currency — and where the number of reposts is a measure of popularity — this kind of gaming the system is inevitable.

In late January, President Trump signed an executive order affecting the privacy rights of non-US citizens with respect to data residing in the US. Here’s the relevant text: “Privacy Act. Agencies shall, to the extent consistent with applicable law, ensure that their privacy policies exclude persons who are not United States citizens or lawful permanent residents from the protections of the Privacy Act regarding personally identifiable information.”

https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/25/presidential-executive-order-enhancing-public-safety-interior-united

At issue is the EU-US Privacy Shield, which is the voluntary agreement among the US government, US companies, and the EU that makes it possible for US companies to store Europeans’ data without having to follow all EU privacy requirements. Interpretations of what this means are all over the place: from extremely serious, to more measured, to don’t worry and we still have PPD-28.

https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/01/26/trump_blows_up_transatlantic_privacy_shield/

https://techcrunch.com/2017/01/26/trump-order-strips-privacy-rights-from-non-u-s-citizens-could-nix-eu-us-data-flows/

https://epic.org/2017/01/trump-administration-limits-sc-1.html

https://www.lawfareblog.com/interior-security-executive-order-privacy-act-and-privacy-shield

This is clearly still in flux. And, like pretty much everything so far in the Trump administration, we have no idea where this is headed.

Attackers held an Austrian hotel network for ransom, demanding $1,800 in bitcoin to unlock the network. Among other things, the locked network wouldn’t allow any of the guests to open their hotel room doors (although this is being disputed). I expect IoT ransomware to become a major area of crime in the next few years. How long before we see this tactic used against cars? Against home thermostats? Within the year is my guess. And as long as the ransom price isn’t too onerous, people will pay.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/30/world/europe/hotel-austria-bitcoin-ransom.html

http://www.thelocal.at/20170128/hotel-ransomed-by-hackers-as-guests-locked-in-rooms

Here’s a story about data from a pacemaker being used as evidence in an arson conviction.

http://www.networkworld.com/article/3162740/security/cops-use-pacemaker-data-as-evidence-to-charge-homeowner-with-arson-insurance-fraud.html

http://www.networkworld.com/article/3162740/

https://boingboing.net/2017/02/01/suspecting-arson-cops-subpoen.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2017/02/08/a-man-detailed-his-escape-from-a-burning-house-his-pacemaker-told-police-a-different-story/

Here’s an article about the US Secret Service and their Cell Phone Forensics Facility in Tulsa.

http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Passcode/2017/0202/Hunting-for-evidence-Secret-Service-unlocks-phone-data-with-force-or-finesse

I said it before and I’ll say it again: the FBI needs technical expertise, not back doors.

In January we learned that a hacker broke into Cellebrite’s network and stole 900GB of data. Now the hacker has dumped some of Cellebrite’s phone-hacking tools on the Internet.

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2017/02/hacker_leaks_ce.html

The Linux encryption app Cryptkeeper has a rather stunning security bug: the single-character decryption key “p” decrypts everything.

https://bugs.debian.org/cgi-bin/bugreport.cgi?bug=852751

https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/01/31/cryptkeeper_cooked/

In 2013, I wrote an essay about how an organization might go about designing a perfect backdoor. This one seems much more like a bad mistake than deliberate action. It’s just too dumb, and too obvious. If anyone actually used Cryptkeeper, it would have been discovered long ago.

https://www.schneier.com/essays/archives/2013/10/how_to_design_and_de.html

Here’s a nice profile of Citizen Lab and its director, Ron Diebert.

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/ron-deiberts-lab-is-the-robin-hood-of-cyber-security

Citizen Lab is a jewel. There should be more of them.

Wired is reporting on a new slot machine hack. A Russian group has reverse-engineered a particular brand of slot machine — from Austrian company Novomatic — and can simulate and predict the pseudo-random number generator.

https://www.wired.com/2017/02/russians-engineer-brilliant-slot-machine-cheat-casinos-no-fix/

The easy solution is to use a random-number generator that accepts local entropy, like Fortuna. But there’s probably no way to easily reprogram those old machines.

https://www.schneier.com/academic/fortuna/

This online safety guide was written for people concerned about being tracked and stalked online. It’s a good resource.

http://chayn.co/safety/

Interesting research: “De-anonymizing Web Browsing Data with Social Networks”:

http://randomwalker.info/publications/browsing-history-deanonymization.pdf

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) published “From Awareness to Action: A Cybersecurity Agenda for the 45th President.” There’s a lot I agree with — and some things I don’t.

https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/170110_Lewis_CyberRecommendationsNextAdministration_Web.pdf

https://www.csis.org/news/cybersecurity-agenda-45th-president

There’s a really interesting paper from George Washington University on hacking back: “Into the Gray Zone: The Private Sector and Active Defense against Cyber Threats.” I’ve never been a fan of hacking back. There’s a reason we no longer issue letters of marque or allow private entities to commit crimes, and hacking back is a form a vigilante justice. But the paper makes a lot of good points.

https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/CCHS-ActiveDefenseReportFINAL.pdf

Here are three older papers on the topic.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2270673

http://ethics.calpoly.edu/hackingback.pdf

http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/articles/pdf/v25/25HarvJLTech429.pdf

Pew Research just published their latest research data on Americans and their views on cybersecurity:

http://www.pewInternet.org/2017/1/26/americans-and-cybersecurity/

Interesting article in “Science” discussing field research on how people are radicalized to become terrorists.

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/355/6323/352.full

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Schneier News

I spoke at the 2016 Blockchain Workshop in Nairobi. Here’s a video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FAskMLNwRPY

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Security and Privacy Guidelines for the Internet of Things

Lately, I have been collecting IoT security and privacy guidelines. Here’s everything I’ve found:

* “Internet of Things (IoT) Broadband Internet Technical Advisory Group, Broadband Internet Technical Advisory Group, Nov 2016.

http://www.bitag.org/documents/BITAG_Report_-_Internet_of_Things_(IoT)_Security_and_Privacy_Recommendations.pdf

* “IoT Security Guidance,” Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP), May 2016.

https://www.owasp.org/index.php/IoT_Security_Guidance

* “Strategic Principles for Securing the Internet of Things (IoT),” US Department of Homeland Security, Nov 2016.

https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Strategic_Principles_for_Securing_the_Internet_of_Things-2016-1115-FINAL_v2-dg11.pdf

* “Security,” OneM2M Technical Specification, Aug 2016.

http://www.onem2m.org/images/files/deliverables/Release2/TR-0008-Security-V2_0_0.pdf

* “Security Solutions,” OneM2M Technical Specification, Aug 2016.

http://onem2m.org/images/files/deliverables/Release2/TS-0003_Security_Solutions-v2_4_1.pdf

* “IoT Security Guidelines Overview Document,” GSM Alliance, Feb 2016.

http://www.gsma.com/connectedliving/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CLP.11-v1.1.pdf

* “IoT Security Guidelines For Service Ecosystems,” GSM Alliance, Feb 2016.

http://www.gsma.com/connectedliving/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CLP.12-v1.0.pdf

* “IoT Security Guidelines for Endpoint Ecosystems,” GSM Alliance, Feb 2016.

http://www.gsma.com/connectedliving/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CLP.13-v1.0.pdf

* “IoT Security Guidelines for Network Operators,” GSM Alliance, Feb 2016.

http://www.gsma.com/connectedliving/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CLP.14-v1.0.pdf

* “Establishing Principles for Internet of Things Security,” IoT Security Foundation, undated.

https://iotsecurityfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IoTSF-Establishing-Principles-for-IoT-Security-Download.pdf

* “IoT Design Manifesto,” www.iotmanifesto.com, May 2015.

https://www.iotmanifesto.com/wp-content/themes/Manifesto/Manifesto.pdf

* “NYC Guidelines for the Internet of Things,” City of New York, undated.

https://iot.cityofnewyork.us/

* “IoT Security Compliance Framework,” IoT Security Foundation, 2016.

https://iotsecurityfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/IoT-Security-Compliance-Framework.pdf

* “Principles, Practices and a Prescription for Responsible IoT and Embedded Systems Development,” IoTIAP, Nov 2016.

http://www.iotiap.com/principles-2016_12_02.html

* “IoT Trust Framework,” Online Trust Alliance, Jan 2017.

http://otalliance.actonsoftware.com/acton/attachment/6361/f-008d/1/-/-/-/-/IoT%20Trust%20Framework.pdf

* “Five Star Automotive Cyber Safety Framework,” I am the Cavalry, Feb 2015.

https://www.iamthecavalry.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Five-Star-Automotive-Cyber-Safety-February-2015.pdf

* “Hippocratic Oath for Connected Medical Devices,” I am the Cavalry, Jan 2016.

https://www.iamthecavalry.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/I-Am-The-Cavalry-Hippocratic-Oath-for-Connected-Medical-Devices.pdf

* “Industrial Internet of Things Volume G4: Security Framework,” Industrial Internet Consortium, 2016.

http://www.iiconsortium.org/pdf/IIC_PUB_G4_V1.00_PB-3.pdf

* “Future-proofing the Connected World: 13 Steps to Developing Secure IoT Products,” Cloud Security Alliance, 2016.

https://downloads.cloudsecurityalliance.org/assets/research/Internet-of-things/future-proofing-the-connected-world.pdf

Other, related, items:

* “We All Live in the Computer Now,” The Netgain Partnership, Oct 2016.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9qOTaXg3UmRZlhWQk5LOUo5Ykk/view

* “Comments of EPIC to the FTC on the Privacy and Security Implications of the Internet of Things,” Electronic Privacy Information Center, Jun 2013.

https://epic.org/privacy/ftc/EPIC-FTC-IoT-Cmts.pdf

* “Internet of Things Software Update Workshop (IoTSU),” Internet Architecture Board, Jun 2016.

https://www.iab.org/activities/workshops/iotsu/

* “Multistakeholder Process; Internet of Things (IoT) Security Upgradability and Patching,” National Telecommunications & Information Administration, Jan 2017.

https://www.ntia.doc.gov/other-publication/2016/multistakeholder-process-iot-security

They all largely say the same things: avoid known vulnerabilities, don’t have insecure defaults, make your systems patchable, and so on.

My guess is that everyone knows that IoT regulation is coming, and is either trying to impose self-regulation to forestall government action or establish principles to influence government action. It’ll be interesting to see how the next few years unfold.

If there are any IoT security or privacy guideline documents that I’m missing, please tell me in email.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Since 1998, CRYPTO-GRAM has been a free monthly newsletter providing summaries, analyses, insights, and commentaries on security: computer and otherwise. You can subscribe, unsubscribe, or change your address on the Web at <https://www.schneier.com/crypto-gram.html>. Back issues are also available at that URL.

Please feel free to forward CRYPTO-GRAM, in whole or in part, to colleagues and friends who will find it valuable. Permission is also granted to reprint CRYPTO-GRAM, as long as it is reprinted in its entirety.

CRYPTO-GRAM is written by Bruce Schneier. Bruce Schneier is an internationally renowned security technologist, called a “security guru” by The Economist. He is the author of 12 books — including “Liars and Outliers: Enabling the Trust Society Needs to Survive” — as well as hundreds of articles, essays, and academic papers. His influential newsletter “Crypto-Gram” and his blog “Schneier on Security” are read by over 250,000 people. He has testified before Congress, is a frequent guest on television and radio, has served on several government committees, and is regularly quoted in the press. Schneier is a fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School, a program fellow at the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute, a board member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an Advisory Board Member of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, and CTO of IBM Resilient and Special Advisor to IBM Security. See <https://www.schneier.com>.

Crypto-Gram is a personal newsletter. Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of Resilient Systems, Inc.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Bruce Schneier.

The takeaways are many. For the projection room it points to more vigilance – faster turnaround on software updates and a sharp eye for additional equipment tied into the network.

Read the whole thing and subscribe to his very readable newsletter at:

CRYPTO-GRAM

February 15, 2017

by Bruce Schneier

CTO, Resilient Systems, Inc.

[email protected]

https://www.schneier.com

A free monthly newsletter providing summaries, analyses, insights, and commentaries on security: computer and otherwise.

For back issues, or to subscribe, visit <https://www.schneier.com/crypto-gram.html>.

You can read this issue on the web at <https://www.schneier.com/crypto-gram/archives/2017/0215.html>. These same essays and news items appear in the “Schneier on Security” blog at <http://www.schneier.com/blog>, along with a lively and intelligent comment section. An RSS feed is available.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

In this issue:

Security and the Internet of Things

News

Schneier News

Security and Privacy Guidelines for the Internet of Things

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Security and the Internet of Things

Last year, on October 21, your digital video recorder — or at least a DVR like yours — knocked Twitter off the Internet. Someone used your DVR, along with millions of insecure webcams, routers, and other connected devices, to launch an attack that started a chain reaction, resulting in Twitter, Reddit, Netflix, and many sites going off the Internet. You probably didn’t realize that your DVR had that kind of power. But it does.

All computers are hackable. This has as much to do with the computer market as it does with the technologies. We prefer our software full of features and inexpensive, at the expense of security and reliability. That your computer can affect the security of Twitter is a market failure. The industry is filled with market failures that, until now, have been largely ignorable. As computers continue to permeate our homes, cars, businesses, these market failures will no longer be tolerable. Our only solution will be regulation, and that regulation will be foisted on us by a government desperate to “do something” in the face of disaster.

In this article I want to outline the problems, both technical and political, and point to some regulatory solutions. “Regulation” might be a dirty word in today’s political climate, but security is the exception to our small-government bias. And as the threats posed by computers become greater and more catastrophic, regulation will be inevitable. So now’s the time to start thinking about it.

We also need to reverse the trend to connect everything to the Internet. And if we risk harm and even death, we need to think twice about what we connect and what we deliberately leave uncomputerized.

If we get this wrong, the computer industry will look like the pharmaceutical industry, or the aircraft industry. But if we get this right, we can maintain the innovative environment of the Internet that has given us so much.

—– —–

We no longer have things with computers embedded in them. We have computers with things attached to them.

Your modern refrigerator is a computer that keeps things cold. Your oven, similarly, is a computer that makes things hot. An ATM is a computer with money inside. Your car is no longer a mechanical device with some computers inside; it’s a computer with four wheels and an engine. Actually, it’s a distributed system of over 100 computers with four wheels and an engine. And, of course, your phones became full-power general-purpose computers in 2007, when the iPhone was introduced.

We wear computers: fitness trackers and computer-enabled medical devices — and, of course, we carry our smartphones everywhere. Our homes have smart thermostats, smart appliances, smart door locks, even smart light bulbs. At work, many of those same smart devices are networked together with CCTV cameras, sensors that detect customer movements, and everything else. Cities are starting to embed smart sensors in roads, streetlights, and sidewalk squares, also smart energy grids and smart transportation networks. A nuclear power plant is really just a computer that produces electricity, and — like everything else we’ve just listed — it’s on the Internet.

The Internet is no longer a web that we connect to. Instead, it’s a computerized, networked, and interconnected world that we live in. This is the future, and what we’re calling the Internet of Things.

Broadly speaking, the Internet of Things has three parts. There are the sensors that collect data about us and our environment: smart thermostats, street and highway sensors, and those ubiquitous smartphones with their motion sensors and GPS location receivers. Then there are the “smarts” that figure out what the data means and what to do about it. This includes all the computer processors on these devices and — increasingly — in the cloud, as well as the memory that stores all of this information. And finally, there are the actuators that affect our environment. The point of a smart thermostat isn’t to record the temperature; it’s to control the furnace and the air conditioner. Driverless cars collect data about the road and the environment to steer themselves safely to their destinations.

You can think of the sensors as the eyes and ears of the Internet. You can think of the actuators as the hands and feet of the Internet. And you can think of the stuff in the middle as the brain. We are building an Internet that senses, thinks, and acts.

This is the classic definition of a robot. We’re building a world-size robot, and we don’t even realize it.

To be sure, it’s not a robot in the classical sense. We think of robots as discrete autonomous entities, with sensors, brain, and actuators all together in a metal shell. The world-size robot is distributed. It doesn’t have a singular body, and parts of it are controlled in different ways by different people. It doesn’t have a central brain, and it has nothing even remotely resembling a consciousness. It doesn’t have a single goal or focus. It’s not even something we deliberately designed. It’s something we have inadvertently built out of the everyday objects we live with and take for granted. It is the extension of our computers and networks into the real world.

This world-size robot is actually more than the Internet of Things. It’s a combination of several decades-old computing trends: mobile computing, cloud computing, always-on computing, huge databases of personal information, the Internet of Things — or, more precisely, cyber-physical systems — autonomy, and artificial intelligence. And while it’s still not very smart, it’ll get smarter. It’ll get more powerful and more capable through all the interconnections we’re building.

It’ll also get much more dangerous.

—– —–

Computer security has been around for almost as long as computers have been. And while it’s true that security wasn’t part of the design of the original Internet, it’s something we have been trying to achieve since its beginning.

I have been working in computer security for over 30 years: first in cryptography, then more generally in computer and network security, and now in general security technology. I have watched computers become ubiquitous, and have seen firsthand the problems — and solutions — of securing these complex machines and systems. I’m telling you all this because what used to be a specialized area of expertise now affects everything. Computer security is now everything security. There’s one critical difference, though: The threats have become greater.

Traditionally, computer security is divided into three categories: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. For the most part, our security concerns have largely centered around confidentiality. We’re concerned about our data and who has access to it — the world of privacy and surveillance, of data theft and misuse.

But threats come in many forms. Availability threats: computer viruses that delete our data, or ransomware that encrypts our data and demands payment for the unlock key. Integrity threats: hackers who can manipulate data entries can do things ranging from changing grades in a class to changing the amount of money in bank accounts. Some of these threats are pretty bad. Hospitals have paid tens of thousands of dollars to criminals whose ransomware encrypted critical medical files. JPMorgan Chase spends half a billion on cybersecurity a year.

Today, the integrity and availability threats are much worse than the confidentiality threats. Once computers start affecting the world in a direct and physical manner, there are real risks to life and property. There is a fundamental difference between crashing your computer and losing your spreadsheet data, and crashing your pacemaker and losing your life. This isn’t hyperbole; recently researchers found serious security vulnerabilities in St. Jude Medical’s implantable heart devices. Give the Internet hands and feet, and it will have the ability to punch and kick.

Take a concrete example: modern cars, those computers on wheels. The steering wheel no longer turns the axles, nor does the accelerator pedal change the speed. Every move you make in a car is processed by a computer, which does the actual controlling. A central computer controls the dashboard. There’s another in the radio. The engine has 20 or so computers. These are all networked, and increasingly autonomous.

Now, let’s start listing the security threats. We don’t want car navigation systems to be used for mass surveillance, or the microphone for mass eavesdropping. We might want it to be used to determine a car’s location in the event of a 911 call, and possibly to collect information about highway congestion. We don’t want people to hack their own cars to bypass emissions-control limitations. We don’t want manufacturers or dealers to be able to do that, either, as Volkswagen did for years. We can imagine wanting to give police the ability to remotely and safely disable a moving car; that would make high-speed chases a thing of the past. But we definitely don’t want hackers to be able to do that. We definitely don’t want them disabling the brakes in every car without warning, at speed. As we make the transition from driver-controlled cars to cars with various driver-assist capabilities to fully driverless cars, we don’t want any of those critical components subverted. We don’t want someone to be able to accidentally crash your car, let alone do it on purpose. And equally, we don’t want them to be able to manipulate the navigation software to change your route, or the door-lock controls to prevent you from opening the door. I could go on.

That’s a lot of different security requirements, and the effects of getting them wrong range from illegal surveillance to extortion by ransomware to mass death.

—– —–

Our computers and smartphones are as secure as they are because companies like Microsoft, Apple, and Google spend a lot of time testing their code before it’s released, and quickly patch vulnerabilities when they’re discovered. Those companies can support large, dedicated teams because those companies make a huge amount of money, either directly or indirectly, from their software — and, in part, compete on its security. Unfortunately, this isn’t true of embedded systems like digital video recorders or home routers. Those systems are sold at a much lower margin, and are often built by offshore third parties. The companies involved simply don’t have the expertise to make them secure.

At a recent hacker conference, a security researcher analyzed 30 home routers and was able to break into half of them, including some of the most popular and common brands. The denial-of-service attacks that forced popular websites like Reddit and Twitter off the Internet last October were enabled by vulnerabilities in devices like webcams and digital video recorders. In August, two security researchers demonstrated a ransomware attack on a smart thermostat.

Even worse, most of these devices don’t have any way to be patched. Companies like Microsoft and Apple continuously deliver security patches to your computers. Some home routers are technically patchable, but in a complicated way that only an expert would attempt. And the only way for you to update the firmware in your hackable DVR is to throw it away and buy a new one.

The market can’t fix this because neither the buyer nor the seller cares. The owners of the webcams and DVRs used in the denial-of-service attacks don’t care. Their devices were cheap to buy, they still work, and they don’t know any of the victims of the attacks. The sellers of those devices don’t care: They’re now selling newer and better models, and the original buyers only cared about price and features. There is no market solution, because the insecurity is what economists call an externality: It’s an effect of the purchasing decision that affects other people. Think of it kind of like invisible pollution.

—– —–

Security is an arms race between attacker and defender. Technology perturbs that arms race by changing the balance between attacker and defender. Understanding how this arms race has unfolded on the Internet is essential to understanding why the world-size robot we’re building is so insecure, and how we might secure it. To that end, I have five truisms, born from what we’ve already learned about computer and Internet security. They will soon affect the security arms race everywhere.

Truism No. 1: On the Internet, attack is easier than defense.

There are many reasons for this, but the most important is the complexity of these systems. More complexity means more people involved, more parts, more interactions, more mistakes in the design and development process, more of everything where hidden insecurities can be found. Computer-security experts like to speak about the attack surface of a system: all the possible points an attacker might target and that must be secured. A complex system means a large attack surface. The defender has to secure the entire attack surface. The attacker just has to find one vulnerability — one unsecured avenue for attack — and gets to choose how and when to attack. It’s simply not a fair battle.

There are other, more general, reasons why attack is easier than defense. Attackers have a natural agility that defenders often lack. They don’t have to worry about laws, and often not about morals or ethics. They don’t have a bureaucracy to contend with, and can more quickly make use of technical innovations. Attackers also have a first-mover advantage. As a society, we’re generally terrible at proactive security; we rarely take preventive security measures until an attack actually happens. So more advantages go to the attacker.

Truism No. 2: Most software is poorly written and insecure.

If complexity isn’t enough, we compound the problem by producing lousy software. Well-written software, like the kind found in airplane avionics, is both expensive and time-consuming to produce. We don’t want that. For the most part, poorly written software has been good enough. We’d all rather live with buggy software than pay the prices good software would require. We don’t mind if our games crash regularly, or our business applications act weird once in a while. Because software has been largely benign, it hasn’t mattered. This has permeated the industry at all levels. At universities, we don’t teach how to code well. Companies don’t reward quality code in the same way they reward fast and cheap. And we consumers don’t demand it.

But poorly written software is riddled with bugs, sometimes as many as one per 1,000 lines of code. Some of them are inherent in the complexity of the software, but most are programming mistakes. Not all bugs are vulnerabilities, but some are.

Truism No. 3: Connecting everything to each other via the Internet will expose new vulnerabilities.

The more we network things together, the more vulnerabilities on one thing will affect other things. On October 21, vulnerabilities in a wide variety of embedded devices were all harnessed together to create what hackers call a botnet. This botnet was used to launch a distributed denial-of-service attack against a company called Dyn. Dyn provided a critical Internet function for many major Internet sites. So when Dyn went down, so did all those popular websites.

These chains of vulnerabilities are everywhere. In 2012, journalist Mat Honan suffered a massive personal hack because of one of them. A vulnerability in his Amazon account allowed hackers to get into his Apple account, which allowed them to get into his Gmail account. And in 2013, the Target Corporation was hacked by someone stealing credentials from its HVAC contractor.

Vulnerabilities like these are particularly hard to fix, because no one system might actually be at fault. It might be the insecure interaction of two individually secure systems.

Truism No. 4: Everybody has to stop the best attackers in the world.

One of the most powerful properties of the Internet is that it allows things to scale. This is true for our ability to access data or control systems or do any of the cool things we use the Internet for, but it’s also true for attacks. In general, fewer attackers can do more damage because of better technology. It’s not just that these modern attackers are more efficient, it’s that the Internet allows attacks to scale to a degree impossible without computers and networks.

This is fundamentally different from what we’re used to. When securing my home against burglars, I am only worried about the burglars who live close enough to my home to consider robbing me. The Internet is different. When I think about the security of my network, I have to be concerned about the best attacker possible, because he’s the one who’s going to create the attack tool that everyone else will use. The attacker that discovered the vulnerability used to attack Dyn released the code to the world, and within a week there were a dozen attack tools using it.

Truism No. 5: Laws inhibit security research.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act is a terrible law that fails at its purpose of preventing widespread piracy of movies and music. To make matters worse, it contains a provision that has critical side effects. According to the law, it is a crime to bypass security mechanisms that protect copyrighted work, even if that bypassing would otherwise be legal. Since all software can be copyrighted, it is arguably illegal to do security research on these devices and to publish the result.

Although the exact contours of the law are arguable, many companies are using this provision of the DMCA to threaten researchers who expose vulnerabilities in their embedded systems. This instills fear in researchers, and has a chilling effect on research, which means two things: (1) Vendors of these devices are more likely to leave them insecure, because no one will notice and they won’t be penalized in the market, and (2) security engineers don’t learn how to do security better.

Unfortunately, companies generally like the DMCA. The provisions against reverse-engineering spare them the embarrassment of having their shoddy security exposed. It also allows them to build proprietary systems that lock out competition. (This is an important one. Right now, your toaster cannot force you to only buy a particular brand of bread. But because of this law and an embedded computer, your Keurig coffee maker can force you to buy a particular brand of coffee.)

—– —–

In general, there are two basic paradigms of security. We can either try to secure something well the first time, or we can make our security agile. The first paradigm comes from the world of dangerous things: from planes, medical devices, buildings. It’s the paradigm that gives us secure design and secure engineering, security testing and certifications, professional licensing, detailed preplanning and complex government approvals, and long times-to-market. It’s security for a world where getting it right is paramount because getting it wrong means people dying.

The second paradigm comes from the fast-moving and heretofore largely benign world of software. In this paradigm, we have rapid prototyping, on-the-fly updates, and continual improvement. In this paradigm, new vulnerabilities are discovered all the time and security disasters regularly happen. Here, we stress survivability, recoverability, mitigation, adaptability, and muddling through. This is security for a world where getting it wrong is okay, as long as you can respond fast enough.